Every year, millions of people in the U.S. take prescription and over-the-counter medications without issue. But for some, a drug that’s supposed to help ends up hurting. A sudden rash. A dangerous drop in blood pressure. Unexplained liver damage. These aren’t rare - they’re adverse drug reactions, and they happen more often than you think. The problem? Most go unreported. That’s a problem because the FDA needs these reports to catch safety issues before more people get hurt.

If you’ve had a bad reaction to a medication - whether you’re a patient, a caregiver, or a healthcare provider - you can and should report it. It’s not just a formality. It’s how the FDA finds out that a drug might be riskier than the label says. And you don’t need to be a doctor to do it. Here’s exactly how to report a suspected adverse drug reaction to the FDA, step by step.

What Counts as a Reportable Adverse Reaction?

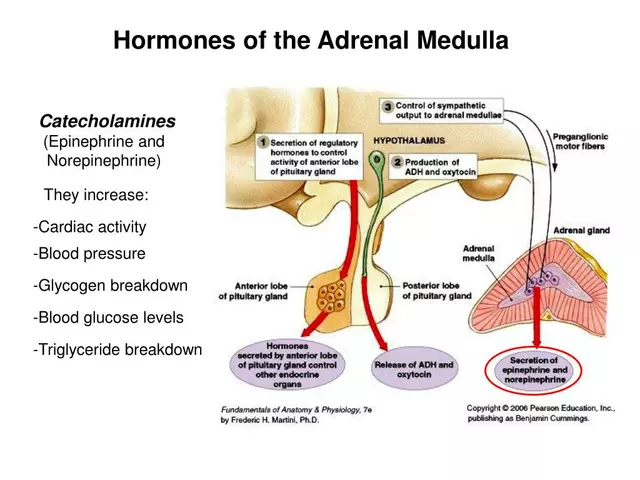

Not every side effect needs a report. The FDA focuses on serious adverse events. These are reactions that are:

- Life-threatening

- Result in hospitalization or prolong an existing hospital stay

- Cause permanent disability or damage

- Lead to a congenital anomaly (birth defect)

- Require medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the above

- Result in death

For example, if you took a new blood pressure medication and ended up in the ER with a heart rhythm problem, that’s reportable. If you got a mild headache that went away after a few hours, it’s probably not. But if you’re unsure, report it anyway. The FDA doesn’t punish people for reporting too much - they need more reports, not fewer.

Even if you’re not 100% sure the drug caused the reaction, report it. The system is built to sort out causality later. One nurse’s report of severe low blood sugar after a new diabetes drug led to a label update in just 47 days. That’s the power of reporting.

Who Can Report?

Anyone can report. You don’t need permission. You don’t need to be a healthcare professional. Patients, family members, nurses, pharmacists, doctors - all of you are part of the safety net.

But there’s a difference in how reports are handled based on who files them:

- Patients and caregivers: You can report voluntarily through MedWatch. No legal obligation, but your report matters.

- Healthcare providers: You’re not required to report unless you’re part of a federally funded registry. But if you suspect a drug caused a serious reaction, you’re strongly encouraged to report - and many hospitals have internal systems to help you do it.

- Pharmaceutical companies: They’re legally required to report serious and unexpected reactions within 15 days. They also have to monitor scientific literature and report anything they find.

The FDA gets about 2 million reports a year. About 40% come from consumers and providers like you. The rest come from drug makers. Your report fills a gap that no lab study or clinical trial ever could.

How to Report: Three Easy Ways

There are three ways to submit a report. The easiest and fastest is online.

1. Report Online via MedWatch (Recommended)

Go to www.fda.gov/medwatch and click on "Report a Problem." You’ll be taken to Form 3500, the official FDA adverse event form.

You’ll need to provide:

- Patient info: Age, sex, weight (if known). You don’t need the full name or address - just enough to identify the person.

- Drug info: Brand name, generic name, dose, how it was taken (pill, injection, etc.), and when you started and stopped taking it.

- Reaction details: What happened, when it started, how long it lasted, how bad it was. Be specific. "Dizziness" isn’t enough. "Felt like the room was spinning for 4 hours after taking the pill, with nausea and blurred vision" is better.

- Outcome: Did it lead to hospitalization? Did it cause permanent harm? Did it resolve?

- Your contact info: So they can follow up if they need more details.

It takes about 20 to 25 minutes to complete. Most people who’ve done it say it’s less confusing than they expected. The system guides you through each section. You can save and come back later if you need to check medical records.

2. Call the FDA

If you’d rather talk to someone, call the MedWatch Safety Information hotline at 1-800-FDA-1088. They’ll walk you through the details over the phone. The average wait time is under 10 minutes. This is a good option if you’re not comfortable typing or if the reaction was very complex.

They’ll take your info and file the report for you. You’ll get a confirmation number. Keep it.

3. Mail a Paper Form

You can download Form 3500 from the MedWatch site, print it, fill it out, and mail it to:

FDA MedWatch

5600 Fishers Lane

Rockville, MD 20852-9787

This method takes longer - up to two weeks for processing - so only use it if you can’t access the internet or phone service. Don’t use this if the reaction was life-threatening and you’re waiting for action.

What Happens After You Report?

Your report goes into the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), a database that’s been collecting safety data since 1969. It’s not a hotline for immediate help - it’s a surveillance tool. But here’s what happens next:

- Reports are reviewed by FDA pharmacovigilance specialists.

- Similar reports are grouped together to spot patterns.

- If enough reports point to the same drug and reaction, the FDA investigates.

- They may require the manufacturer to update the drug label, issue a warning, or even pull the drug from the market.

It’s not instant. But it’s powerful. In 2022, a report from a patient about unusual bleeding with a new anticoagulant led to a safety alert within 60 days. That alert saved lives.

The FDA doesn’t confirm every report. They don’t need to. They’re looking for signals - repeated patterns that suggest a real risk. One report might not do much. But 50 reports? 200? That’s a red flag.

Common Mistakes People Make

Even when people want to report, they often mess up the details. Here’s what to avoid:

- Using vague terms: Don’t say "I felt bad." Say "I had chest pain that started 2 hours after taking the pill and lasted 45 minutes, with sweating and shortness of breath."

- Forgetting the drug name: If you don’t know the generic name, write the brand name. If you don’t know the dose, write "one pill daily" or "as needed."

- Waiting too long: If it’s a serious reaction, report it as soon as you can. The 15-day window applies to manufacturers, but your report still matters more the sooner it’s in.

- Thinking it’s not important enough: The FDA estimates only 6% of serious adverse events are reported. That means 94% go unnoticed. Your report could be the one that triggers a change.

Also, don’t wait for your doctor to report it. Many doctors are too busy. A 2022 survey found that 63% of healthcare providers said they didn’t report because they didn’t have time. Don’t rely on someone else to do it for you.

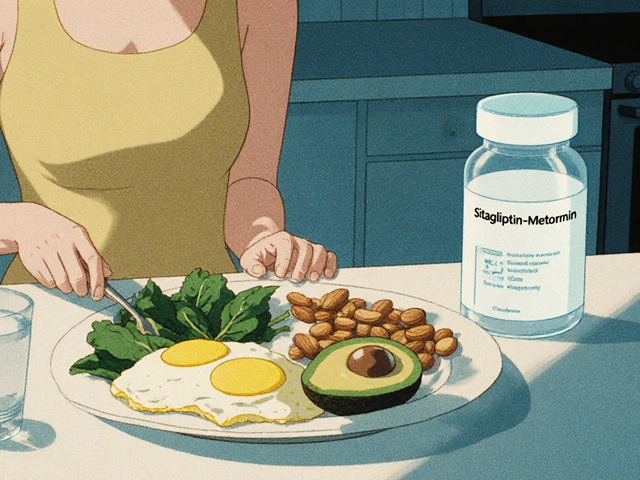

What About Over-the-Counter Drugs and Supplements?

Yes, you can report reactions to OTC drugs like ibuprofen, allergy meds, or sleep aids. You can also report reactions to vitamins, herbal supplements, and dietary products. The FDA doesn’t regulate supplements as strictly as prescription drugs, but they still track safety issues. A 2023 report on a liver injury linked to a popular weight-loss supplement led to a warning and product recall.

Don’t assume supplements are safe just because they’re "natural." They can interact with other drugs or cause serious harm. Report them just like any other medication.

Why Your Report Matters

Drug safety isn’t just about clinical trials. Those trials involve a few thousand people. Once a drug hits the market, millions use it. Different ages, different health conditions, different combinations of medications. That’s when hidden risks show up.

The FDA’s system is designed to catch those risks - but only if people report them. Without your report, a drug could keep being prescribed to people who shouldn’t take it. Someone else could end up in the hospital because no one spoke up.

Dr. Alastair Wood, a former FDA safety expert, said only 5-10% of serious adverse events are reported. That means we’re missing the vast majority. Every report you file increases the chance that a dangerous pattern will be spotted - and fixed.

This isn’t about blaming drug companies. It’s about making sure drugs are as safe as possible for everyone. Your report doesn’t just help you - it helps the next person who takes that same pill.

What’s Changing in the Future?

The FDA is working to make reporting easier and more accurate. By the end of 2025, electronic health record systems will be required to send adverse event data directly to the FDA. That means doctors won’t have to manually file reports - the system will do it automatically.

They’re also testing blockchain to verify reports and prevent fake submissions. And starting in 2024, they’ll begin collecting reports from social media - like posts on Reddit or Facebook where people describe bad reactions.

These changes are coming because the old system, while good, is too slow. The goal is to catch dangers faster. But until then, your report still makes a difference.

Do I need to tell my doctor before reporting to the FDA?

No, you don’t need to tell your doctor first. You can report directly to the FDA without their approval or involvement. However, it’s still a good idea to let your doctor know about the reaction so they can adjust your treatment. But if you’re worried about the drug’s safety, don’t wait for your doctor to act - report it yourself.

Will my report be kept private?

Yes. The FDA protects your identity. Your name, address, and contact details are not made public. The data in the FAERS database is anonymized and used only for safety analysis. Only the FDA and authorized researchers can access personal information, and they’re legally required to keep it confidential.

Can I report a reaction that happened years ago?

Yes, you can. The FDA accepts reports regardless of when the reaction occurred. While timely reports are more useful for catching emerging risks, older reports can still help identify long-term patterns - especially if the drug is still in use. Don’t let the time gap stop you.

What if I report and nothing happens?

Nothing happening doesn’t mean your report didn’t matter. The FDA reviews hundreds of thousands of reports every year. One report might not trigger an action, but it adds to the overall signal. If enough people report the same issue, the FDA will act. Your report is part of a larger picture.

Is reporting only for prescription drugs?

No. You can report reactions to over-the-counter medications, vitamins, herbal supplements, and even cosmetics. The FDA tracks safety for all products it regulates. If you had a bad reaction to a supplement, sunscreen, or acne cream, report it. These products are often assumed to be safe, but they can still cause harm.

How long does it take for the FDA to act on a report?

There’s no set timeline. Some reports lead to quick warnings - like the 47-day label update after a hypoglycemia report. Others take months or years if the signal is weak or mixed with other data. The FDA doesn’t notify individual reporters when they act, but you can check the FDA’s website for safety alerts on the drug you reported.

Can I report a reaction from a drug I took in another country?

Yes. If the drug was sold in the U.S. - even if you took it overseas - you can report it. The FDA tracks all products that are marketed in the United States, regardless of where the reaction occurred. This helps them understand global safety patterns.

Next Steps: What to Do Now

If you’ve had a bad reaction to a drug, don’t wait. Don’t assume someone else will report it. Don’t think it’s too small. Go to www.fda.gov/medwatch right now. Take five minutes. Fill out Form 3500. It’s that simple.

If you’re a healthcare provider, make reporting part of your routine. Add it to your checklist after every new prescription. Talk to your patients about it. They might not know they can report - and they might not know how important it is.

Drug safety isn’t just the FDA’s job. It’s everyone’s job. Your report could be the one that saves a life - maybe even your own next time.

The FDA's pharmacovigilance infrastructure remains a profoundly underutilized public good. Most adverse event reports are submitted with insufficient clinical granularity-vague descriptors like 'feeling weird' or 'bad reaction' render the data noise rather than signal. To truly contribute meaningfully, reporters must articulate temporal relationships between drug administration and symptom onset with the precision of a clinical note. I've reviewed thousands of entries in FAERS; the ones that trigger regulatory action are invariably those that include duration, dose titration, concomitant medications, and objective findings like lab values or ECG changes. If you're going to report, don't just file a form-construct a case.

I reported my husband's reaction to his new blood pressure med after he collapsed in the kitchen. Took me three days to gather the details, but I did it. I didn't know it mattered. Now I know it does. Thank you for writing this.

bro this is so important 😍 i took some ayurvedic weight loss powder last year and got liver issues, no one told me to report it but now i know 🙏 also why dont they make a simple app for this? like 3 taps and done? 🤔

They don't want you to know how many drugs are quietly killing people. The pharma lobby owns the FDA. Report all you want-nothing changes until the public wakes up.

There's a quiet, almost sacred act in reporting an adverse reaction-it’s the moment you choose solidarity over silence. You’re not just documenting a personal trauma; you’re inserting your lived experience into the vast, impersonal machinery of public health. It’s a radical act of care, really. You’re saying: 'This happened to me, but it shouldn’t happen to anyone else.' And in that simple declaration, you become part of a lineage of ordinary people who, through stubborn attention to detail, forced institutions to see what they’d rather ignore. We are the eyes the system forgot to install.

This is a vital guide that deserves global dissemination. In India, where polypharmacy is common and regulatory awareness is low, many patients suffer in silence due to misinformation. I have shared this with my community health group and encouraged all caregivers to report even minor anomalies. The FDA’s system, though American, transcends borders-especially when drugs are sourced internationally. We must normalize this practice as part of responsible healthcare consumption. Thank you for the clarity and urgency in your writing.

Just reported my niece's rash after her new allergy med. Took 15 mins. Felt good. Hope it helps someone.

If you're reading this and you've ever had a bad reaction to anything-even if you think it was 'just a headache'-you owe it to the next person to report it. Not because it's your duty. Not because the FDA asked. But because someone else’s child, parent, or friend might be taking that same pill tomorrow. And you? You’re the only one who knows what it felt like. That’s power. Use it.

From a pharmacovigilance standpoint, the current FAERS system suffers from significant reporting bias: patients with severe outcomes are more likely to report, while mild but persistent reactions-like chronic fatigue or cognitive fog-are systematically underrepresented. This skews signal detection algorithms toward acute, dramatic events, leaving insidious, long-term toxicities undetected for years. The upcoming EHR integration is promising, but only if it captures longitudinal data, not just isolated events. We need structured, interoperable reporting that includes patient-reported outcomes, medication adherence logs, and comorbidities-not just a checkbox form. Until then, the burden remains on the individual to articulate the inarticulable.