When a brand-name drug hits the market, it doesn’t stay alone for long. But how long does it get to be alone? That’s where patent exclusivity comes in - and it’s not the same everywhere. In the U.S., a generic drug maker might wait 12 years before it can launch a cheaper version. In the EU, it could be 10. In some countries, it’s even longer. These rules aren’t just legal fine print - they control who gets access to affordable medicine and how much pharmaceutical companies earn. And the differences between countries aren’t random. They’re the result of decades of lobbying, court battles, and public health debates.

How Long Do Patents Last? It’s Not What You Think

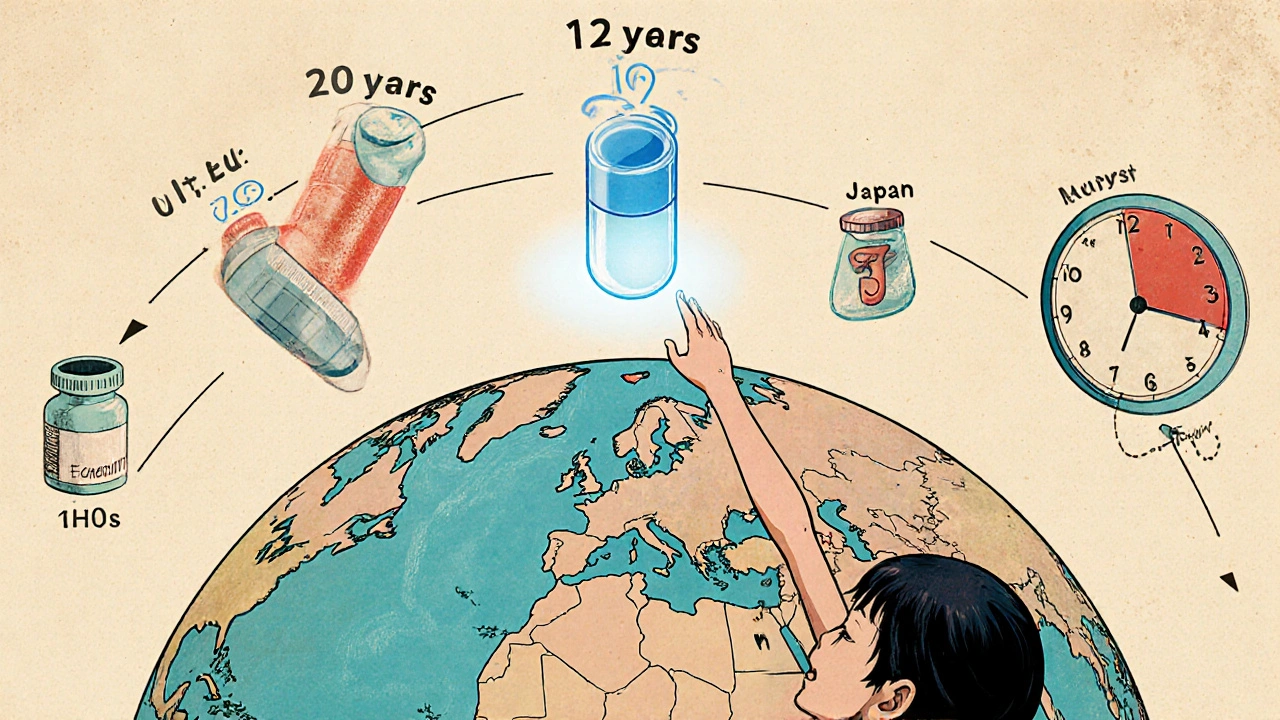

Most people assume a drug patent lasts 20 years. That’s true on paper - the TRIPS Agreement, signed by nearly every country, sets the global baseline at 20 years from the filing date. But here’s the catch: drug development takes 10 to 12 years before the drug even reaches patients. That means by the time a drug is approved, only 6 to 10 years of patent life remain. That’s not enough to recoup the $2.3 billion it typically costs to bring a new drug to market, according to Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development.

To fix this, countries built extensions. The U.S. uses Patent Term Extension (PTE), which can add up to 5 years, but with a hard cap: total protected time after approval can’t exceed 14 years. The EU does something similar with Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs). Both systems are designed to give companies a fair shot at recovering R&D costs. But here’s where it gets messy: these extensions are only available for the first approval of a new active ingredient. If a company tweaks the drug slightly - say, changes the dosage form or adds a new indication - it can file new patents. This is called “evergreening,” and it’s a major reason why some drugs have over 100 patents attached to them.

The U.S. System: A Maze of Exclusivity

The U.S. doesn’t just rely on patents. It layers on regulatory exclusivity - rules that block generics from even applying for approval, regardless of patent status. The most important one is the 5-year New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity. If a drug contains a brand-new active ingredient, no generic can submit an application for five years. After that, generics can file, but they still have to deal with patents.

Then there’s the 180-day exclusivity - the golden ticket for generic companies. The first generic to successfully challenge a patent under the Hatch-Waxman Act gets 180 days of market exclusivity. No other generic can enter during that time. That’s a huge incentive. But it’s also a loophole. Sometimes, brand companies pay generics to delay entry - known as “pay-for-delay.” The FTC has fought these deals for years, and courts have ruled them illegal in many cases, but they still happen.

Other exclusivities include 7 years for orphan drugs (rare disease treatments), 3 years for new clinical studies, and 6 months for pediatric testing. These can stack. A single drug might have 5 different exclusivities running at once. That’s why some drugs stay monopoly-priced for over a decade, even after the core patent expires.

The EU System: More Predictable, Less Flexible

Europe’s approach is simpler, but not necessarily fairer. It uses an “8+2+1” model. For 8 years, generic companies can’t even use the originator’s clinical trial data to prove their drug works. That’s called data exclusivity. Then, for another 2 years, they can’t sell their version - even if they’ve built their own data. That’s market exclusivity. Finally, if the originator proves their drug has a significant clinical benefit, they get an extra year.

There’s no 180-day exclusivity for first filers. No patent challenges with financial rewards. That means generic companies in Europe enter the market more slowly and less aggressively. It also means fewer legal battles. But it also means less pressure on brand companies to innovate - or to lower prices. The EU’s system is more predictable, which helps generics plan. But it also gives originators longer, quieter monopolies.

Canada, Japan, and Other Countries: What’s the Pattern?

Canada follows the EU model closely: 8 years of data exclusivity, plus 2 years of market protection. Japan is stricter - 8 years of data exclusivity and 4 years of market protection for new chemical entities. China raised its data exclusivity from 6 to 12 years in 2020. Brazil went to 10 years in 2021. These aren’t random changes. They’re responses to trade deals and pressure from big pharma.

The real problem shows up in low-income countries. The World Health Organization found that essential medicines reach generic status 19.3 years after approval in poor nations - nearly 7 years longer than in rich ones. Why? Because trade agreements like CETA or the USMCA force developing countries to adopt strict data exclusivity rules, even when patents have expired. That means people in South Africa might wait 11 extra years for a generic HIV drug because of a European trade deal.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

Brand companies win. Merck says its cancer drug Keytruda’s effective market life was extended from 8.2 to 12.7 years through patents and exclusivity. That’s billions in revenue. Generic makers win too - but only the ones who can afford the legal battles. Teva says originator drugs now have an average of 142 patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. That’s a wall. Only deep-pocketed generics can climb it.

Patients lose when generics are delayed. IQVIA found that once generics enter, brand drug prices drop 80-90% within a year. But if the first generic is blocked by a pay-for-delay deal, that price drop never happens. A 2023 American Pharmacists Association survey found 78% of pharmacists saw delays for three or more drugs in the past year. That’s not just inconvenient - it’s life-or-death for people on insulin, blood thinners, or HIV meds.

And then there’s the innovation argument. PhRMA says without strong exclusivity, drug development would collapse. But Harvard’s Dr. Aaron Kesselheim found originator companies file an average of 38 additional patents per drug - many on trivial changes. Is that innovation? Or just legal gaming?

What’s Changing in 2025?

The U.S. is trying to crack down on pay-for-delay with the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act. The EU is considering cutting data exclusivity from 8 to 5 years for some drugs. Japan is speeding up its patent review process. But big pharma is fighting back hard. The International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations says 97% of its members believe the current system is essential.

The real question isn’t whether exclusivity should exist. It’s how long it should last - and who it’s really protecting. If the goal is to reward real innovation and ensure affordable access, then today’s patchwork system is failing. Too many drugs are locked away for years after their patents expire. Too many people can’t afford the medicine they need.

As $356 billion in branded drug sales face expiration between 2023 and 2028, the pressure is rising. Governments can’t afford to keep letting legal loopholes delay generic entry. The science is there. The demand is there. The only thing missing is the will to fix the rules.

So let me get this straight - we’re supposed to believe that 12 years of exclusivity is ‘fair’ when the actual R&D cost is mostly sunk by year 5? The real monopoly isn’t the patent, it’s the regulatory maze designed to keep generics out. This isn’t innovation protection - it’s rent-seeking dressed up as policy.

I’ve worked with patients who can’t afford their meds even with insurance, and I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen someone skip doses because the generic didn’t come out yet. The system isn’t broken because it’s too generous - it’s broken because it’s too clever. Every extra year of exclusivity is another year someone’s life is on hold. It’s not just about dollars, it’s about dignity. We’ve got the science, we’ve got the will, we just need the courage to say: enough.

why do we even care about patents anymore like its 1990s and big pharma is still running the show i mean come on its not like they invent stuff anymore they just tweak the pill color and call it new and then charge 10x and then sue everyone who tries to make it cheaper its just greed plain and simple

So the EU does 8+2+1 and calls it ‘predictable’? Bro, that’s just ‘predictably slow’. Meanwhile in the US we’ve got a legal wrestling match where the first generic to win gets a 180-day gold pass - like a VIP ticket to monopoly profits. It’s capitalism with a side of chaos. And don’t get me started on pay-for-delay - that’s not a business model, that’s a hostage situation with pill bottles.

Let’s be real - this whole system is a Rube Goldberg machine built by lawyers with PhDs in loopholes. You’ve got patents, data exclusivity, pediatric extensions, orphan drug bonuses, and then - boom - you stack ‘em like Jenga blocks until the whole thing collapses under its own weight. And the kicker? The people who need the meds the most? They’re the ones getting kicked out of the game. We’re not protecting innovation here. We’re protecting profit margins with a velvet glove and a steel trap.

This is all a psyop. Big Pharma owns the FDA, the WHO, and half the Congress. The ‘12-year’ number? Fabricated. The ‘R&D cost’? Inflated. The ‘patents’? Just a distraction. They’re using this to keep prices high so they can fund their private islands and offshore accounts. And the ‘generic makers’? They’re just the other side of the same coin - waiting for their turn to become the new monopolists. Wake up. This isn’t about medicine. It’s about control.

The key here is understanding the difference between patent term and regulatory exclusivity. Patents are IP - exclusivity is administrative. The Hatch-Waxman Act was designed to balance access and incentive, but the layers have become unmanageable. Pay-for-delay is anticompetitive, yes - but the real issue is the lack of transparency in patent listings. The Orange Book is a minefield. We need mandatory public disclosure of all patent claims, with penalties for frivolous filings. That’s where reform should start.

in india we see this every day - people wait years for generics because of trade deals they didn’t even vote on. my uncle needed insulin and had to import from bangladesh because local generics were blocked by some EU clause. this isn’t science, it’s politics with a pill bottle label.

The current regulatory framework, while complex, is structured to align with international intellectual property norms under the TRIPS Agreement, thereby ensuring compliance with global trade obligations. The extension mechanisms, including Supplementary Protection Certificates and Patent Term Extensions, are legally codified to incentivize pharmaceutical innovation through the provision of a sufficient period of market exclusivity, which is empirically correlated with increased R&D investment. Disruption of these mechanisms without alternative funding models may result in a reduction of novel therapeutic development.