When someone you love is using drugs, the fear of an overdose isn’t just a thought-it’s a real, ticking clock. You might have seen them nod off after using, or heard them gasping for air, and wondered if this time was different. The truth is, most overdoses happen at home, and family members are often the first-and sometimes only-people who can act. Teaching your family how to recognize the signs of an overdose isn’t about scaring them. It’s about giving them the power to save a life.

What an Overdose Actually Looks Like

People often confuse being high with overdosing. That’s dangerous. Someone who’s high might be sleepy, giggly, or sluggish-but they’ll still respond if you shake them or shout their name. Someone who’s overdosing won’t. Not even a little. For opioid overdoses-like those from heroin, fentanyl, or prescription painkillers-the signs are clear and urgent:- Unresponsive: Shout their name. Shake their shoulder. Rub your knuckles hard on their sternum. If they don’t move, react, or open their eyes, that’s a red flag.

- Slow or stopped breathing: Watch their chest. Are they taking fewer than one breath every five seconds? Or worse-no breath at all? This is the most critical sign.

- Blue or gray lips and fingertips: On lighter skin, this looks like blue or purple. On darker skin, it’s more like ashen gray or dull purple. Don’t wait for the classic blue-gray is just as deadly.

- A limp body, like a ragdoll.

- Clammy, cold skin.

- A gurgling or snoring sound-like they’re drowning in their own saliva. That’s called the “death rattle.”

- Extreme high body temperature (over 104°F).

- Seizures or violent shaking.

- Chest pain or racing heartbeat.

- Confusion, paranoia, or aggression.

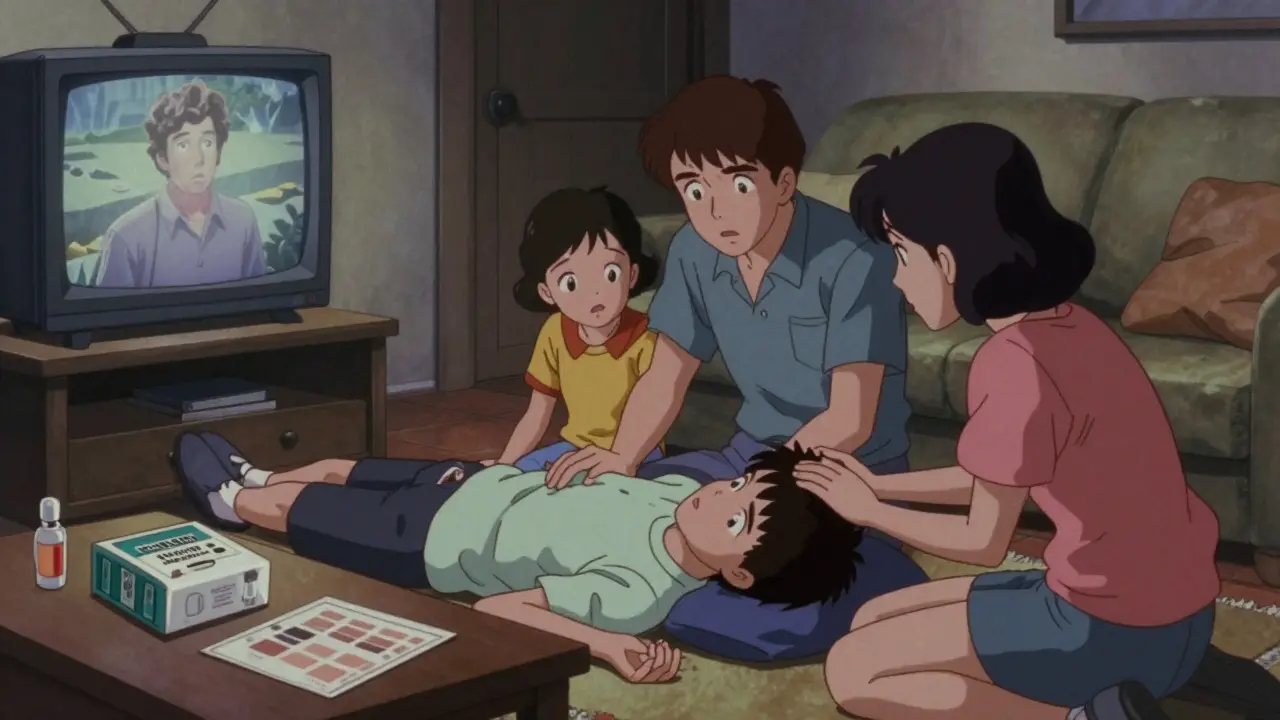

Why Practice Makes the Difference

Reading about overdose signs isn’t enough. In a real emergency, your body goes into panic mode. Your mind blanks. That’s why training with real tools changes everything. Studies show that families who practice with training naloxone kits remember 89% of what they learn after three months. Those who only watch videos or listen to lectures? Only 42% recall the steps. That’s more than double the chance of saving a life. Here’s how to practice:- Get a training naloxone kit. These cost about $35 and come with a dummy injector-no medicine inside. You can get them free from local harm reduction programs or pharmacies in many states.

- Use a mannequin or a pillow. Practice giving the injection into the outer thigh, just like you would on a person. Push until you hear a click. Hold it for five seconds.

- Run scenarios. One person pretends to be unconscious. Others practice checking breathing, calling 999, and administering the naloxone. Do this three times. Don’t stop until it feels automatic.

How to Talk About It Without Scaring People

Talking about overdose can feel heavy. People worry it’ll make things worse. They think, “If I bring it up, maybe it’ll happen.” That’s a myth. Studies show families who talk about overdose are more likely to keep their loved ones safe. Start simple. Say: “I care about you. If something happens, I want to know what to do. Let’s learn together.” Use real examples. “I read that 78% of overdoses happen at home. That means if something goes wrong, we’re the ones who can help.” Don’t wait for a crisis. Do it when things are calm. Maybe after watching a documentary, or when a news story comes on. Make it part of your family’s safety plan-like knowing where the fire extinguisher is.

What to Do When You See the Signs

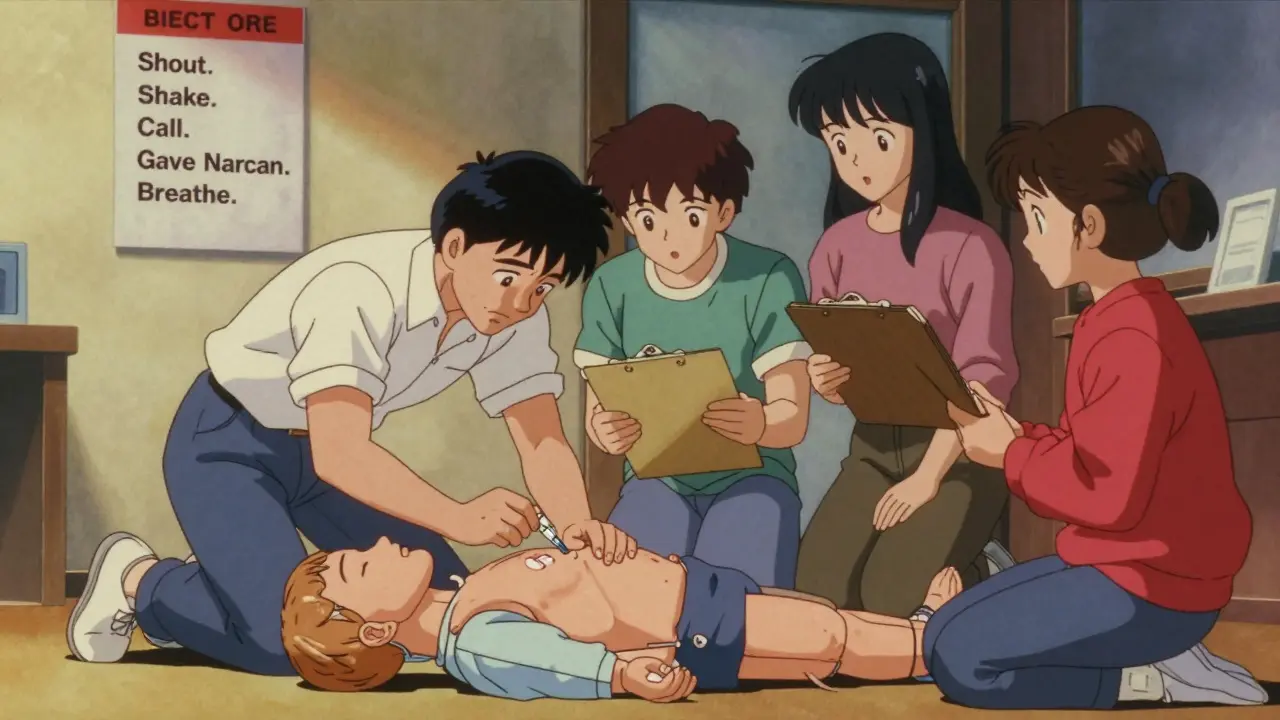

If you suspect an overdose, don’t wait. Don’t try to wake them with cold water or coffee. Don’t leave them alone. Follow these steps:- Shout and shake: Try to wake them. If no response, move to step two.

- Call 999: Say, “I think someone is overdosing.” Don’t apologize. Don’t explain. Just say it. Emergency services will come, even if drugs are involved.

- Give naloxone: Use the training kit you practiced with. Inject into the thigh. One dose. Wait 2-3 minutes.

- Start rescue breathing: If they’re not breathing, tilt their head back, pinch their nose, and give one breath every five seconds. Keep going until they breathe on their own or help arrives.

- Give a second dose if needed: If they don’t respond after 3 minutes, give another naloxone dose. Fentanyl is strong-sometimes one shot isn’t enough.

What You Need to Get Started

You don’t need a lot to be ready:- Training naloxone kit: Get one from your local pharmacy, health clinic, or harm reduction center. Many are free.

- Skin tone guide: Print or save a picture showing how blue/gray looks on different skin tones. This helps avoid misreading symptoms.

- Emergency card: Write down the steps on a small card: “Shout. Shake. Call 999. Give Narcan. Breathe.” Keep it in your wallet or phone case.

- Access to free resources: The Overdose Lifeline app has video tutorials and step-by-step guides. The CDC’s website has printable checklists.

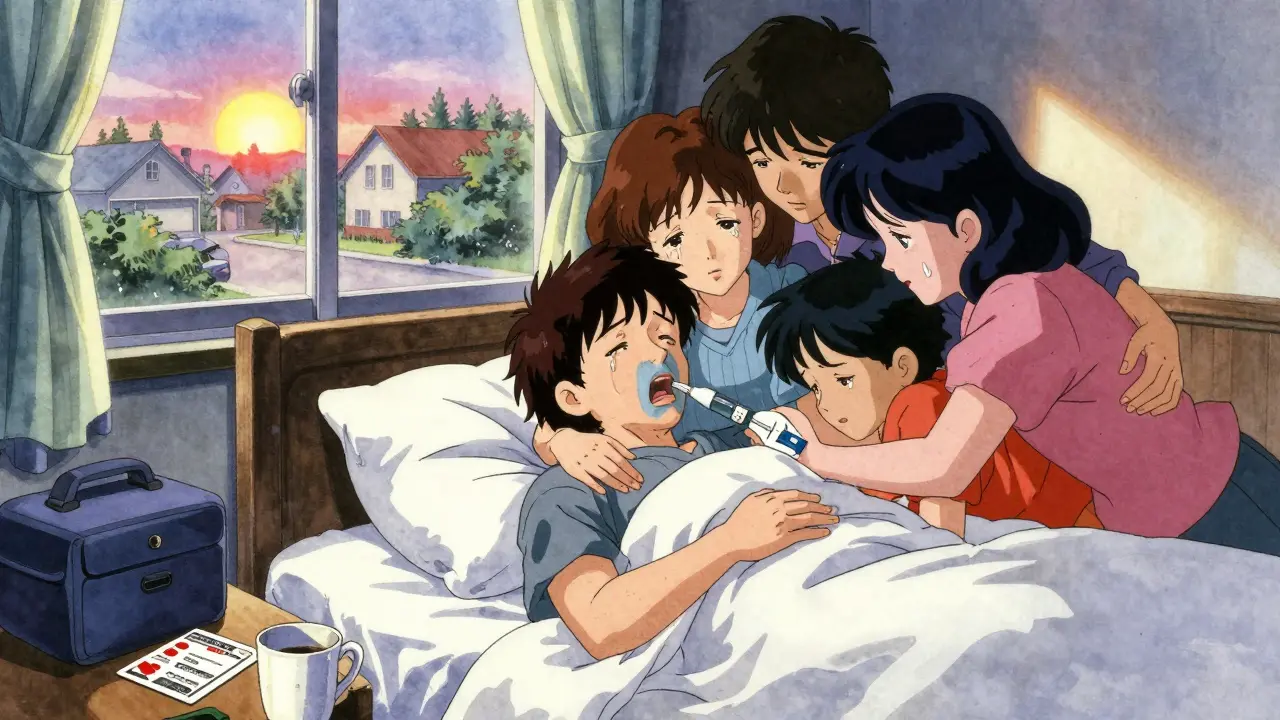

What Happens After You Save a Life

If you use naloxone and they wake up, they might be angry. They might yell. They might say, “Why did you do that?” That’s normal. Their brain is flooded with chemicals. They’re scared. They’re in withdrawal. Don’t take it personally. Say: “I didn’t want to lose you. I love you. I’m here.” Then, make sure they get medical help-even if they feel fine. Naloxone wears off in 30-90 minutes. If opioids are still in their system, they can slip back into overdose. And after? Talk about next steps. Maybe it’s therapy. Maybe it’s a support group. Maybe it’s just knowing they’re not alone.It’s Not About Judgment. It’s About Survival.

This isn’t about whether someone “deserves” to live. It’s not about right or wrong. It’s about the fact that your family member is still here-and you have the tools to keep them that way. In the UK, over 4,000 people die from drug overdoses every year. Most of them are alone. But they don’t have to be. With a little training, your home can become a place of safety, not fear. You don’t need to be a doctor. You don’t need to understand every drug. You just need to know what to look for-and what to do. Start today. Practice with someone. Keep the kit in the same place as your first aid supplies. Talk about it like you would fire safety or car accidents. Because when it matters most, you won’t have time to read a book. You’ll need to act. And you will.Can naloxone be used on anyone, even if they didn’t take opioids?

Yes. Naloxone only works on opioids and has no effect on other drugs like cocaine, meth, or alcohol. It’s safe to use even if you’re unsure. Giving it to someone who didn’t take opioids won’t harm them-it just won’t do anything. When in doubt, give it.

What if I’m scared to call 999 because I’m worried about legal trouble?

In the UK, there’s a legal protection called the Good Samaritan law. If you call for help during an overdose, you and the person overdosing are protected from prosecution for drug possession. Emergency services are there to save lives, not punish. Calling 999 is the single most important step you can take.

How long does naloxone last, and do I need more than one dose?

Naloxone usually works for 30 to 90 minutes. But many drugs, especially fentanyl, last much longer. If the person wakes up but then slips back into unresponsiveness, give a second dose. Always have at least two doses available. Many kits come with two nasal sprays for exactly this reason.

Can I train my kids to recognize overdose signs?

Yes. Children as young as 10 can learn to recognize unresponsiveness and call for help. You don’t need to teach them how to use naloxone, but they can learn to shout for help, check breathing, and stay with the person until adults arrive. Practice with them like you would a fire drill.

Where can I get free naloxone and training in the UK?

You can get free naloxone and training from local harm reduction services, community pharmacies, or NHS sexual health clinics. In Manchester, organizations like the Manchester Drug and Alcohol Action Team (MDAAT) offer free kits and workshops. Visit their website or call your local pharmacy and ask for overdose prevention resources.

Is it true that fentanyl is making overdoses harder to spot?

Fentanyl doesn’t change the signs-it just makes them come faster and stronger. People can overdose within minutes, even from a tiny amount. That’s why practicing the steps is so important. You won’t have time to look up symptoms. You need to act fast. Training helps you react before panic sets in.

Okay but like… I literally just watched my cousin OD last year and we had NO idea what to do. 😭 I thought he was just passed out drunk. Then his lips turned gray and I screamed. We called 999 but he was already blue. Please, if you’re reading this-learn this stuff. I don’t want anyone else to go through that.

There’s a deeper truth here: society treats addiction as a moral failure, not a medical crisis. But saving a life doesn’t require judgment-it requires readiness. The fact that we need to teach families how to reverse overdoses says more about our broken systems than it does about individual choices. Still… this guide? Necessary. Practical. Human.

i just read this and i think it’s really important. i didn’t know about the skin tone thing. i’ll print that out and keep it with my first aid kit. thanks for sharing. 😊

From a harm reduction standpoint, this is textbook-tier education. The emphasis on motor memory through simulation with training kits is evidence-based best practice-89% retention vs. 42% from passive learning? That’s a massive delta. Pair that with the de-stigmatized framing and you’ve got a scalable public health intervention. Also, the emergency card? Genius. Analog redundancy in crisis scenarios is non-negotiable.

Oh great, now we’re turning every living room into an ER. Next you’ll be handing out Narcan with the Christmas cards. People need to stop being addicts and start being responsible. This isn’t babysitting-it’s enabling. And don’t get me started on letting kids ‘practice’-what’s next, teaching toddlers how to clean a syringe?

Okay so I just did this with my mom last weekend-like, full-on drill. We used a pillow, I yelled ‘JESSICA!’ at the top of my lungs, she ‘passed out’ on the couch, I gave the fake injection, called 999 on speakerphone, and did rescue breathing while humming ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ because I panicked and forgot the rhythm. We laughed so hard we cried. Then we did it again. And again. Now I actually know what to do. And honestly? It feels less scary now. Like… we’re not helpless. We’re prepared. That’s everything.

How quaint. You assume everyone has access to a $35 training kit, a pharmacy that doesn’t judge, or a healthcare system that doesn’t abandon them. This is performative compassion for the middle class. Meanwhile, in rural India, families still bury their children with no one to call, no naloxone to administer, and no one to care. Your ‘safety plan’ is a luxury. This post reads like a TED Talk for the privileged.

My brother’s been clean for 3 years now, but I still keep the Narcan in the kitchen drawer next to the fire extinguisher. We don’t talk about it much-but we know it’s there. And that matters. You don’t need to be brave to save a life. You just need to be ready. Thanks for writing this.

YESSSSS. This is the kind of info that should be taught in schools. Like, right next to sex ed and CPR. And to the person who said ‘enabling’-no. This is survival. Naloxone is not a reward for bad choices-it’s a reset button. And if you’re scared to call 999? Good Samaritan laws exist for a reason. DO NOT WAIT. I’ve used Narcan twice. Both times, the person woke up crying, hugging me, and saying ‘I’m sorry.’ That’s not enabling. That’s love in action. 💪❤️