Every year, hundreds of thousands of older adults in the U.S. wake up confused, withdrawn, or agitated after starting a new medication. It’s not dementia. It’s not just aging. It’s medication-induced delirium-a sudden, dangerous mental shift that’s often missed, misunderstood, and entirely preventable.

What Medication-Induced Delirium Really Looks Like

Delirium isn’t just being forgetful. It’s a rapid, fluctuating change in awareness, attention, and thinking that shows up over hours or days. An older person who was sharp and alert on Monday might be quiet, unresponsive, or staring blankly by Wednesday. Or they might be restless, yelling at imaginary people, or trying to pull out their IV line. These aren’t personality changes-they’re brain changes caused by drugs. There are three types. The hyperactive kind is loud and obvious: pacing, hallucinating, fighting. The hypoactive kind? That’s the silent killer. The person just sits there-slowed down, uninterested, barely speaking. They look tired. Depressed. Like they’ve given up. But it’s not depression. It’s delirium. And it’s the most common form in older adults, making up 72% of cases. That’s why so many get missed. The biggest red flag? A sudden change. Not gradual. Not slow. Within 48 hours of starting a new pill, a caregiver will often say, “It’s like a different person.” That’s not normal aging. That’s a warning sign.Which Medications Are the Biggest Culprits?

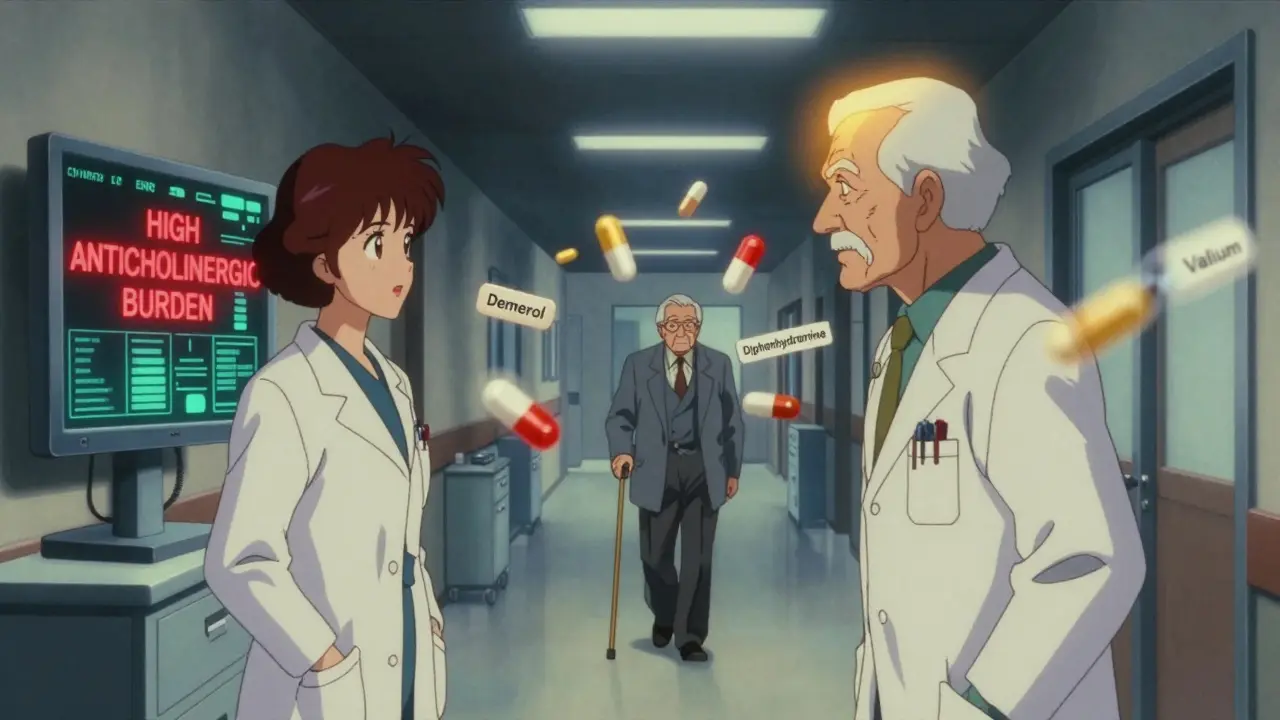

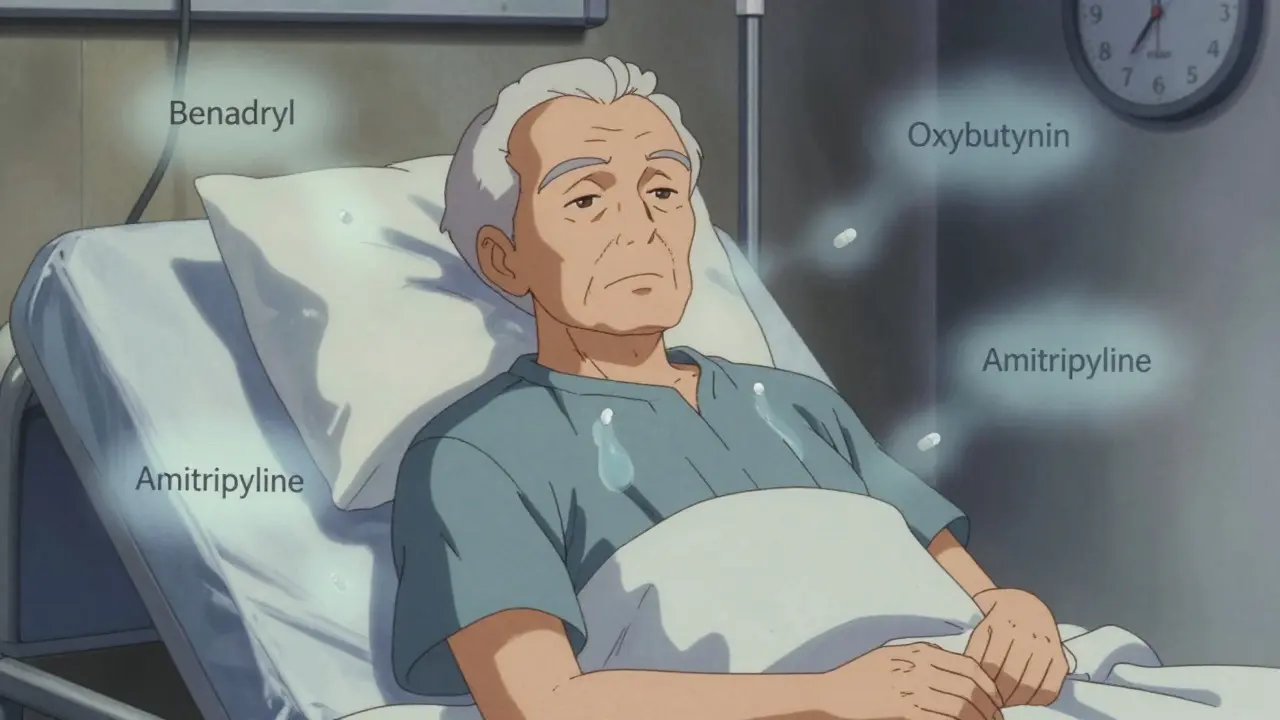

Not all drugs are equal. Some are far more likely to trigger delirium-and many are still routinely prescribed to older adults. Anticholinergic drugs are the top offenders. These block acetylcholine, a brain chemical critical for memory and focus. Common examples include:- Diphenhydramine (Benadryl)-still sold as a sleep aid or allergy pill

- Oxybutynin-for overactive bladder

- Amitriptyline-for nerve pain or depression

- Hyoscine (for motion sickness)

Why This Happens: The Brain on Drugs

As we age, our brains change. The blood-brain barrier gets leakier. The liver and kidneys don’t clear drugs as fast. Brain cells become more sensitive to chemical shifts. A drug that’s fine for a 40-year-old can overload an 80-year-old’s brain. Anticholinergics don’t just cause confusion-they disrupt the brain’s ability to filter information. Imagine trying to listen to one person in a crowded room, but every voice is screaming. That’s what it’s like for someone in delirium. Their brain can’t focus. It’s overwhelmed. Benzodiazepines calm the brain too much. They suppress the very systems that keep you alert and oriented. That’s why people on these drugs seem “calm”-but they’re not present. They’re mentally fogged. And here’s the cruel twist: people with dementia are 2.5 times more likely to get delirium from these drugs. And once they do, the episode lasts nearly twice as long-8.2 days on average. That’s not just confusion. That’s accelerated decline.How to Prevent It Before It Starts

The good news? Medication-induced delirium is one of the most preventable conditions in older adults. Here’s how:- Do a full medication review. Every time a senior sees a doctor, ask: “What’s this for? Can we stop any of these?” Use the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale (ACB). A score of 3 or higher means high risk. Many seniors have scores of 5 or 6 without realizing it.

- Avoid anticholinergics entirely if possible. Swap Benadryl for loratadine. Swap oxybutynin for mirabegron. Swap amitriptyline for duloxetine or gabapentin if treating nerve pain.

- Use benzodiazepines only in emergencies. No routine use for sleep or anxiety. If absolutely needed, use short-acting lorazepam over long-acting diazepam-and never for more than a few days.

- Choose safer pain meds. Start with acetaminophen. Add non-drug options like heat, massage, or distraction. If opioids are needed, hydromorphone is better than morphine.

- Watch for withdrawal. Stopping a benzodiazepine too fast can trigger delirium tremens. Taper slowly over 7-14 days.

What Families and Caregivers Can Do

You’re the first line of defense. You know your loved one’s normal. If something changes fast-especially after a new prescription-speak up.- Keep a list of every pill, patch, and supplement they take-including over-the-counter ones.

- Ask the pharmacist: “Is this drug on the Beers Criteria list?”

- If they’re in the hospital, ask: “Are you screening for delirium?” Most don’t.

- Don’t accept “It’s just old age” or “She’s always been forgetful.”

- Use the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)-it’s free, simple, and takes two minutes. Look for: sudden change, inattention, disorganized thinking, altered awareness.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Delirium isn’t just uncomfortable. It’s deadly. People who have it are twice as likely to die within a year. Their hospital stays are eight days longer on average. They’re far more likely to end up in a nursing home. And their cognitive decline doesn’t stop after they leave the hospital. The U.S. spends $164 billion a year treating complications from delirium. That’s not just money-it’s lost independence, lost time, lost dignity. And here’s the shocking part: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) now calls hospital-acquired delirium a “never event.” That means hospitals don’t get paid for treating it. They’re supposed to prevent it. But only 68% of hospitals have formal prevention programs. And only 18% check anticholinergic burden systematically. That’s not progress. That’s negligence.What’s Changing Now

Good news: things are shifting. The FDA now requires stronger warnings on anticholinergic labels. The National Institute on Aging is funding real-time EHR alerts to flag high-risk combinations. AI tools are being tested to predict delirium risk before a drug is even given. But change moves slowly. Until then, the power is in your hands. If you’re caring for an older adult, don’t wait for the system to fix itself. Ask the questions. Push for safer options. Say no to the pills that don’t belong. Delirium doesn’t have to happen. It’s not inevitable. It’s not just part of aging. It’s a medical error-and it’s preventable.Can medication-induced delirium be reversed?

Yes, in most cases. Once the triggering medication is stopped or reduced, symptoms often improve within days to weeks. But recovery depends on how long the delirium lasted, the person’s overall health, and whether they had pre-existing dementia. The sooner the drug is identified and removed, the better the outcome.

Is delirium the same as dementia?

No. Dementia is slow, progressive, and usually permanent. Delirium is sudden, fluctuating, and often reversible. Someone with dementia can still have delirium on top of it-and that’s dangerous. Delirium can make dementia symptoms seem worse than they are, leading to misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatments.

Why is hypoactive delirium so often missed?

Because it looks like tiredness, depression, or just “slowing down.” The person isn’t yelling or agitated-they’re quiet, withdrawn, and unresponsive. Staff and families assume they’re just getting older. But this form is the most common and the most deadly. It’s not laziness. It’s brain dysfunction.

Are over-the-counter drugs safe for seniors?

Not always. Many OTC sleep aids, cold medicines, and allergy pills contain diphenhydramine or other strong anticholinergics. A single Benadryl tablet can be enough to trigger delirium in someone over 75. Always check labels and ask a pharmacist before giving any OTC drug to an older adult.

What should I do if I suspect delirium in a loved one?

Act fast. Review all medications taken in the last 72 hours. Call their doctor or go to urgent care. Don’t wait. Bring a complete list of all drugs, including supplements. Say: “I think this might be medication-induced delirium.” Early intervention can prevent lasting damage.

Okay but have you seen the ads for Benadryl on TV? It’s literally marketed as a ‘sleep aid’ for seniors. Meanwhile, grandma’s in the ER because she took two for ‘just a little allergy’ and now she’s yelling at the ceiling fan. The pharmaceutical industry doesn’t want you to know this stuff-they make BILLIONS off these prescriptions. It’s not negligence. It’s profit.

I’ve seen this firsthand. My dad was on five anticholinergics-Benadryl, oxybutynin, amitriptyline, gabapentin (which isn’t even on the list but still messes with his head), and a weird patch for motion sickness. One day he stopped recognizing me. We thought it was dementia. Turned out? It was just a drug cocktail from hell. Took three weeks to clear his system. He’s back to his old self now. Don’t wait until it’s too late. Ask the questions. Even if they roll their eyes.

USA still letting Big Pharma poison our elders? 😒 We in Nigeria? We don’t even have enough meds-but if we did, we’d NEVER give an old person Benadryl for sleep. Our grandmas take ginger tea and sleep like babies. This is not ‘medicine.’ This is colonial mentality with a prescription pad. Shame on you, American doctors.

Simple truth: if a drug makes you feel weird, stop it. If you’re confused after a new pill, it’s probably the pill. No magic. No mystery. Just biology. Ask your pharmacist. They’re not just there to hand out bottles-they’re trained to catch this stuff. Use them.

My mom had hypoactive delirium for 11 days after her knee surgery. They called it ‘post-op fatigue.’ I cried because she wouldn’t look at me. When we finally stopped her anticholinergic meds, she woke up like she’d been asleep for a year. I’m so glad this post exists. Please share it with every caregiver you know.

People who give their parents Benadryl for sleep are just lazy. You want them quiet? Then sit with them. Read to them. Play their favorite music. Not poison them with chemicals because you can’t handle being present. This isn’t healthcare-it’s emotional avoidance wrapped in a pill.

Let me tell you something real: I used to work in a nursing home. We had a woman who hadn’t spoken in weeks. Then we pulled her oxybutynin and her amitriptyline. She asked for her daughter’s name. Then she asked for pie. That’s it. That’s the whole story. One pill change. One pie. One life returned. You don’t need a PhD to fix this. You just need to care enough to check the list.

Benadryl = brain fog. Period.

It is imperative that healthcare providers adopt standardized screening protocols for anticholinergic burden in geriatric populations. The Hospital Elder Life Program has demonstrated statistically significant reductions in delirium incidence, and its implementation should be considered a standard of care. Furthermore, electronic health record integration of the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale is not merely beneficial-it is ethically obligatory.

I used to think aging meant slowing down. Then I watched my aunt go from knitting sweaters to staring at walls after her doctor added a new ‘sleep aid.’ It broke my heart. But when we took it away? She started humming again. She didn’t need more pills. She needed someone to listen. Maybe that’s the real medicine we’ve forgotten.

My mother-in-law was on 7 meds. We cut 4. Her energy came back. She started gardening again. No drama. No miracle. Just removing the things that were poisoning her brain. If you’re caring for someone older, do a med review. It’s the most powerful thing you can do.