When your pharmacist hands you a generic pill instead of the brand-name version, you might wonder: is this really the same thing? The answer isn’t as simple as "yes" or "no"-but it’s far more precise than most people realize. The term "bioequivalent" isn’t marketing jargon. It’s a strict, science-backed standard that tells you, with high confidence, that the generic version will work in your body just like the brand-name drug. And it’s why 9 out of 10 prescriptions filled in the U.S. are generics.

What bioequivalence actually means

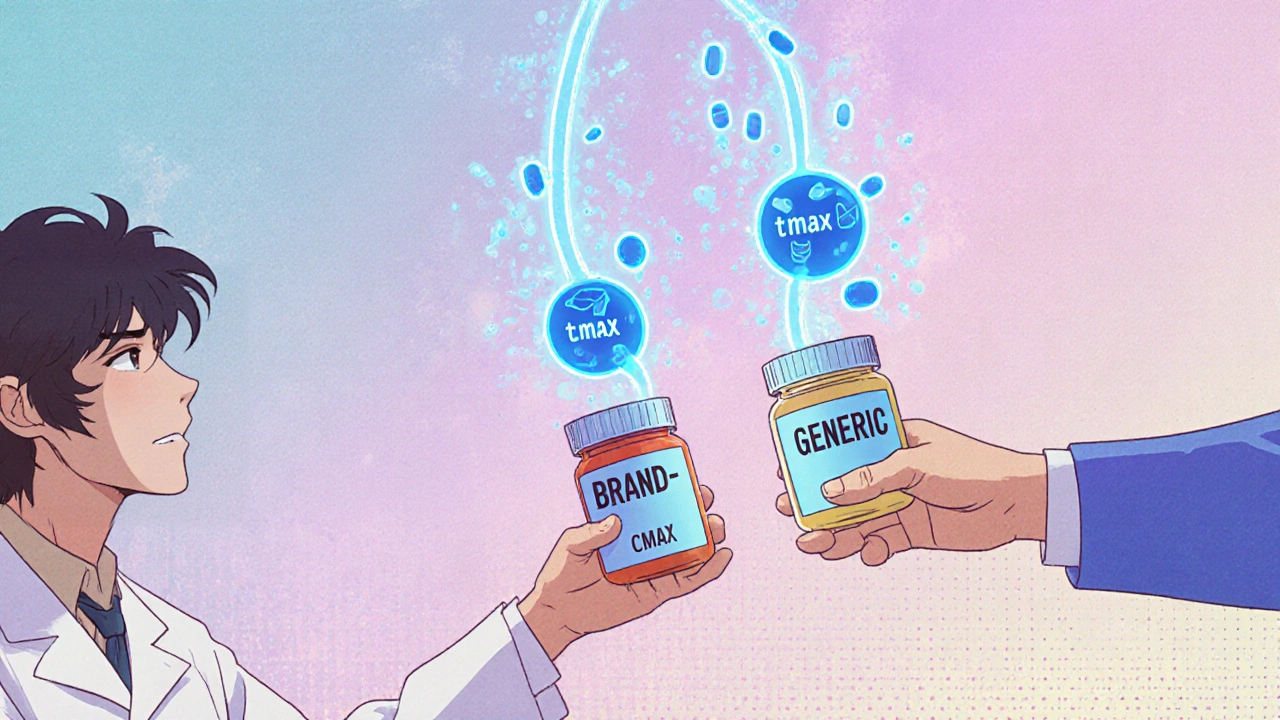

Bioequivalence doesn’t mean two drugs are chemically identical. It means they deliver the same active ingredient to your bloodstream at the same rate and in the same amount. Think of it like two different routes to the same destination: one might be a highway, the other a backroad, but if you arrive at the same time with the same amount of fuel left, the trip worked the same way. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines bioequivalence as the absence of a significant difference in how quickly and how much of the drug enters your system. That’s measured using three key numbers: Cmax (the highest concentration in your blood), tmax (how long it takes to get there), and AUC (the total exposure over time). For a generic to be approved, the 90% confidence interval for these values must fall between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug’s results. That’s not a random range-it’s based on decades of data showing that differences smaller than 20% don’t affect how well the drug works or how safe it is for most people.How bioequivalence is tested

Before a generic drug hits the shelf, it goes through human studies. Usually, 24 to 36 healthy volunteers take both the brand-name and generic versions, at different times, under controlled conditions-often fasting. Blood samples are taken over several hours to track how the drug moves through their bodies. The data is then compared statistically. This isn’t a simple test. Some drugs are harder to measure because they’re absorbed inconsistently, especially if taken with food. For those, the FDA might require testing under both fed and fasted states. Complex products like inhalers, nasal sprays, or topical creams can’t be measured through blood tests alone. For those, manufacturers might use in vitro tests, clinical endpoint studies, or even patient-reported outcomes to prove equivalence.Bioequivalence vs. pharmaceutical equivalence vs. therapeutic equivalence

These terms get mixed up a lot. Here’s how they differ:- Pharmaceutical equivalence means both drugs have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration. They could still have different fillers, colors, or coatings.

- Bioequivalence means they perform the same in your body-same absorption, same timing, same exposure.

- Therapeutic equivalence is the gold standard. It means the drugs are both pharmaceutical and bioequivalent, and can be safely swapped without any expected change in effectiveness or safety. The FDA labels these as "AB-rated" in the Orange Book, which lists all approved generic drugs and their equivalence status.

Why the 80-125% range matters

Some people hear "80% to 125%" and think that’s too wide. But here’s the key: it’s not about the average difference-it’s about statistical certainty. The FDA doesn’t just look at the mean. It requires that 90% of the time, the difference falls within that range. That means even in the worst-case scenario, you’re still getting 80% of the drug exposure you’d get from the brand. For most medications, that’s plenty. There are exceptions. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-where the difference between a helpful dose and a toxic one is tiny-the rules tighten. For example, with blood thinners like warfarin or seizure meds like phenytoin, the acceptable range shrinks to 90-111%. These are the drugs where even small changes can cause real problems. That’s why pharmacists often recommend sticking with the same generic manufacturer once you’ve started-because even within generics, small differences in inactive ingredients can affect absorption.Real-world evidence: do generics work?

Critics point to rare cases where patients report differences after switching-especially with antiepileptic drugs. A 2021 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that 0.8% of patients on generic antiepileptics had breakthrough seizures after switching. That sounds alarming, but consider this: the FDA reviewed over 2,000 generic applications and found 98.7% of them had AUC values within 90-110% of the brand. That’s incredibly consistent. A 2022 survey of over 1,200 independent pharmacists found that 87% saw no clinically significant differences between brand and generic drugs for most conditions. Consumer Reports’ 2023 survey of 3,421 patients showed 78% were satisfied with generics, compared to 82% for brand-name drugs. The biggest gap? Antiepileptics-where satisfaction dropped to 70%. That’s why many states now require pharmacies to notify patients or get consent before switching those specific drugs. And here’s something surprising: adverse event reports for generic drugs make up only 0.3% of all drug-related reports to the FDA’s system-exactly what you’d expect given that generics make up 90% of prescriptions. If they were unsafe, the numbers would be way higher.

Cost and impact

Bioequivalence isn’t just about science-it’s about savings. Developing a generic drug, including bioequivalence testing, costs around $2.2 million. That’s a fraction of the $1-2 billion it takes to bring a new brand-name drug to market. Because of this, generic drugs save the average patient $313 per prescription. Over the last decade, generics have saved the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $2.2 trillion. Globally, the generic drug market is worth over $400 billion and is growing fast. But standards vary. The European Medicines Agency allows wider ranges (75-133%) for highly variable drugs. The FDA is updating its guidance for complex products like inhalers and topical creams, with 27 new documents released since 2020. And in 2023, the FDA committed $25 million over the next four years to improve bioequivalence methods for these harder-to-measure drugs.What you should do

If you’re prescribed a generic drug, you can feel confident-most of the time, it’s just as effective. But if you’re on a narrow therapeutic index drug (like levothyroxine, warfarin, or phenytoin), pay attention:- Ask your pharmacist if the generic is AB-rated.

- If you’ve been stable on a specific brand or generic, ask to stay on it.

- Report any changes in how you feel after a switch-especially with seizure meds, thyroid meds, or blood thinners.

- Don’t assume all generics are identical. Even within the same drug, different manufacturers can use different fillers that affect absorption.

Are generic drugs as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes, for the vast majority of medications. Generic drugs must meet the same strict bioequivalence standards as brand-name drugs, meaning they deliver the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same rate. The FDA requires that the 90% confidence interval for absorption (AUC and Cmax) falls between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug. Studies show that 98.7% of approved generics fall within 90-110% of the reference, which is considered clinically equivalent.

What does "AB-rated" mean on a generic drug label?

"AB-rated" means the generic drug has been approved by the FDA as both pharmaceutical and bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. This rating is listed in the FDA’s Orange Book and indicates the drug can be substituted for the brand without expecting any difference in effectiveness or safety. Not all generics are AB-rated-some may be rated "BX," meaning bioequivalence hasn’t been proven or the drug is too complex to compare using standard methods.

Why do some people say generics don’t work as well?

A small number of patients report differences, especially with drugs that have a narrow therapeutic index-like levothyroxine, warfarin, or phenytoin. These drugs require very precise dosing, and even minor changes in absorption can cause symptoms. In these cases, differences in inactive ingredients (like fillers or coatings) between generic manufacturers may affect how the drug is absorbed. That’s why pharmacists often recommend sticking with the same generic manufacturer once you’ve started. For most other medications, these reports are rare and not supported by clinical data.

Is bioequivalence testing the same worldwide?

No. The U.S. FDA uses an 80-125% range for most drugs, while the European Medicines Agency allows wider ranges (75-133%) for highly variable drugs. The FDA typically tests under fasting conditions, but the EU often requires testing under both fed and fasted states. These differences mean a generic approved in one country may not automatically be approved in another, even if it’s the same product.

Can I trust a generic drug that’s much cheaper than the brand?

Yes-if it’s FDA-approved and AB-rated. The cost difference comes from lower research, marketing, and development expenses, not lower quality. Generic manufacturers must meet the same manufacturing standards as brand-name companies. The average cost to develop a generic drug is $2.2 million, and about 30-40% of that goes to bioequivalence testing. A low price doesn’t mean a low standard.

Do bioequivalence standards apply to all types of medications?

Not always. For drugs that act locally-like inhalers, nasal sprays, or topical creams-bioequivalence can’t be measured through blood levels. Instead, manufacturers use in vitro tests, clinical endpoint studies, or pharmacodynamic measurements to prove the drug works the same way. The FDA has issued over 27 guidance documents since 2020 to address these complex products, ensuring they meet the same safety and effectiveness standards.

Look, I don’t care what the FDA says-I switched to a generic for my blood pressure med and felt like a ghost for a week. Something’s off.

Generic meds work fine for most people, but if you’re on warfarin or levothyroxine, stick with the same brand or manufacturer-switching even between generics can mess with your INR or TSH levels. I’ve seen it in clinic. Not worth the risk.

It’s amazing how much science goes into something most people just assume is ‘the same pill.’ The 80-125% range isn’t arbitrary-it’s based on real-world outcomes. Trust the data, not the fear.

Yeah right the FDA approves generics but they’re still just cheap knockoffs with different fillers that make people feel weird. You think they care about your thyroid when they’re making millions off brand names? No way. The whole system is rigged

You know, I’ve always thought of bioequivalence like two different poets reciting the same poem-one in a deep baritone, one in a soft alto-but the meaning, the rhythm, the emotional weight, it’s all still there. The words are the same, the delivery is just… different. And sometimes, that difference matters, especially if you’re sensitive to tone. I’ve been on the same generic levothyroxine for five years now. My doctor says it’s AB-rated, and I feel fine. But I’d never switch brands unless I had to. It’s not about distrust-it’s about knowing your own body’s whisper.

Brilliantly articulated. The 80-125% range is a triumph of statistical pragmatism, not a loophole. In the UK, we’ve used generics for decades without issue-except, of course, for the occasional patient who insists the blue pill makes them ‘feel funny’ and refuses to explain why. The science is solid; the psychology? Not so much.

AB-rated is the gold standard, but don’t forget BX-rated drugs-those are the ones you need to watch. Some topical antifungals, inhalers, even certain injectables fall into that gray zone. Just because it’s generic doesn’t mean it’s interchangeable. Always check the Orange Book.

For people in developing countries, generics are life-saving. I come from India, where 95% of prescriptions are generics, and the quality control is actually very strict under CDSCO. The real issue isn’t the science-it’s access and education. If people knew how rigorously these are tested, they’d stop fearing them.

My mom switched to a generic thyroid med and started having panic attacks-turned out the new filler was triggering her IBS, which messed with absorption. She went back to the brand, and boom, back to normal. So yeah, generics work… but your body might not like the ‘extras.’ Always monitor, always talk to your pharmacist. 💪