Warfarin Dosing Calculator

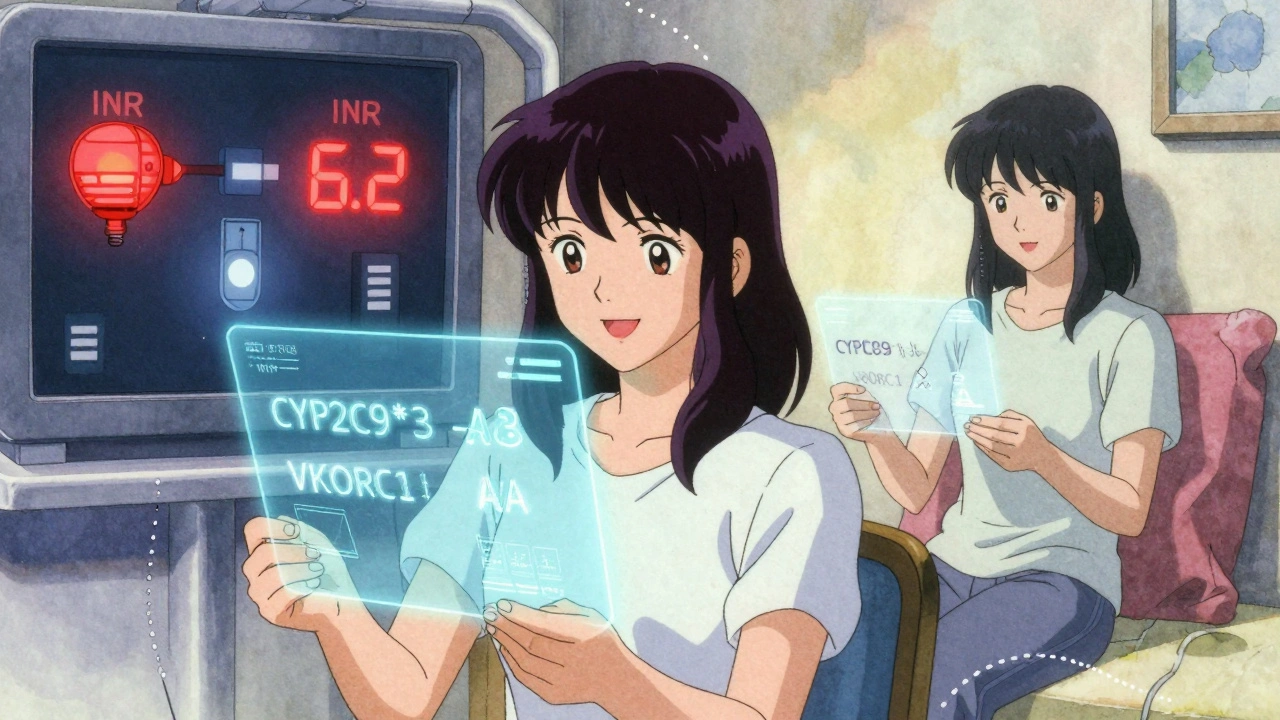

Every year, millions of people start taking warfarin to prevent dangerous blood clots. But for a drug that’s been around since the 1950s, it’s surprisingly hard to get right. Too little, and you’re at risk of stroke. Too much, and you could bleed out from a minor bump. The difference between life and a hospital trip often comes down to a few genetic letters in your DNA - specifically, variations in two genes: CYP2C9 and VKORC1.

Why Warfarin Is So Hard to Dose

Warfarin works by blocking VKORC1, the enzyme your body needs to recycle vitamin K - a key ingredient for making blood clotting proteins. Without enough active vitamin K, your blood thins. Simple enough, right? But here’s the catch: the amount of warfarin one person needs can be wildly different from another’s. Two people, same weight, same age, same condition - one might need 3 mg a day, the other 10 mg. That’s not a mistake. That’s genetics.

For decades, doctors guessed the right dose based on age, weight, diet, and other meds. But even the best guess was wrong half the time. Studies show most patients spend nearly half their first few weeks with INR levels too high or too low. That’s when bleeding or clotting risks spike. And it’s not just inconvenient - it’s dangerous.

The Two Genes That Control Your Warfarin Response

There are two genetic players that explain most of this variability. The first is VKORC1. This gene tells your body how much of the warfarin target enzyme to make. The most common variant, called VKORC1 -1639G>A (rs9923231), changes how sensitive you are to the drug. If you have two copies of the A allele (AA genotype), your body makes far less of the enzyme. That means even a small dose of warfarin can over-thin your blood. People with AA genotypes often need just 5-7 mg per week. Those with GG? They might need 28-42 mg per week. That’s a six-fold difference.

The second gene is CYP2C9. This one handles how fast your liver breaks down warfarin - especially the more powerful S-enantiomer, which is five times stronger than the R-form. Two common variants, CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3, slow this process way down. If you carry the *3 variant, your body clears S-warfarin 80% slower than someone without it. That means the drug builds up in your system, increasing bleeding risk even at standard doses.

Together, these two genes explain about 40-50% of why warfarin doses vary so much. That’s more than age, weight, or diet combined. And it’s not theoretical - it shows up in real patient outcomes.

What Happens When You Don’t Know Your Genotype

Consider this: a 2018 study in the Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis found that 68% of patients with a CYP2C9 variant had at least one INR above 4 in their first three months. That’s a red flag for serious bleeding. Only 42% of patients without the variant had the same issue. And those with the variant were almost twice as likely to need medical care for bleeding.

One Reddit user, u/WarfarinWarrior, shared how their story changed after genetic testing. They’d been on 5 mg daily for six months, bouncing between INR 2 and 7. After finding they had the CYP2C9*3 variant, their dose dropped to 2.5 mg - and their INR finally stabilized. Another user, u/ClottingConfused, didn’t get tested. Their doctor started them at the standard dose. Two weeks later, they ended up in the ER with an INR of 6.2. That’s a level where spontaneous bleeding becomes a real threat.

These aren’t rare cases. A 2022 survey of over 1,200 warfarin users found that 74% of those who had genetic testing reported higher satisfaction with their treatment. Those without testing? Only 62% were happy. The difference wasn’t just about peace of mind - it was about fewer emergency visits and less fear.

Does Genetic Testing Actually Help?

The evidence says yes - but not everyone agrees.

The EU-PACT trial in 2013 showed that patients who got dosing guided by their genes spent 7.7% more time in the safe INR range during the first 90 days. Major bleeding events dropped by 32%. A 2025 meta-analysis in the European Heart Journal confirmed this, finding a 27% reduction in major bleeding with genotype-guided dosing.

But here’s the twist: not all guidelines recommend it. The American College of Chest Physicians says the benefit isn’t strong enough to justify routine testing. Their argument? You’d need to test 200 people to prevent one major bleed. That’s expensive. And in a world where DOACs like apixaban and rivaroxaban are easier to use, why bother?

But DOACs aren’t perfect. They’re expensive. They can’t be reversed easily. And if you have a mechanical heart valve? Warfarin is still the only option. For people who need it long-term - say, 5, 10, 15 years - the cumulative risk of bleeding adds up. That’s where genetics matters most.

Who Should Get Tested?

Testing isn’t for everyone. But it’s strongly recommended if:

- You’re starting warfarin for atrial fibrillation, deep vein thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism

- You’ve had a bad reaction to warfarin before - like an INR over 6 or a bleed

- You’re young and healthy, and you’ll be on it for years

- You’re on other meds that interact with warfarin, like amiodarone or sulfamethoxazole

- You’re of Asian descent - VKORC1 -1639A is much more common in this group

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) gives clear dosing guidelines based on genotype. For example:

- CYP2C9*1/*1 + VKORC1 GG → High dose (5-7 mg/day)

- CYP2C9*1/*3 + VKORC1 AA → Low dose (0.5-2 mg/day)

- CYP2C9*3/*3 + VKORC1 AA → Very low dose (0.5 mg/day or less)

These aren’t guesses. They’re based on data from tens of thousands of patients. And hospitals like Vanderbilt have shown that using this system cuts the time to reach a stable INR by nearly two days.

Cost, Access, and Real-World Barriers

Testing costs $250-$500 in the U.S. Medicare covers it under CPT codes 81225 and 81227. Private insurers? Not always. A 2022 survey found 61% of patients struggled to get coverage. That’s a huge barrier.

Even when the test is done, many doctors don’t know how to use the results. A 2023 study showed only 38% of primary care doctors could correctly explain how CYP2C9*3 affects warfarin metabolism. That’s a problem. A genetic report means nothing if the prescriber doesn’t understand it.

Turnaround time is usually 3-5 business days. That’s fast enough to inform the first dose. But in busy clinics, it often gets delayed or ignored. The real win comes when the test result is built into the electronic health record - so the system automatically flags a low dose for someone with AA/*3.

The Future: More Testing, Less Guesswork

The warfarin genetics market is growing fast. The global pharmacogenetic testing market is projected to hit $14.8 billion by 2029. Warfarin testing makes up 12-15% of that. And costs are falling. By 2027, tests could drop below $100.

New initiatives like the Warfarin Genotype Implementation Network (WaGIN), launched in 2025, aim to enroll 50,000 patients across 200 U.S. sites. Their goal? Prove that when testing is routine, bleeding rates drop - and hospitals save money.

The 2025 American Society of Hematology guidelines, expected in June, are likely to strengthen recommendations for testing in high-risk groups. And with DOACs still not suitable for everyone, warfarin isn’t going away. It’s just getting smarter.

If you’re on warfarin - or about to start - ask your doctor: Have I been tested for CYP2C9 and VKORC1? If not, why not? The answer might save you a trip to the ER - or worse.

What are CYP2C9 and VKORC1?

CYP2C9 is a liver enzyme that breaks down the active form of warfarin. VKORC1 is the enzyme that warfarin blocks to thin your blood. Variants in these genes change how much drug you need and how quickly it builds up in your body.

Can I get tested for these genes?

Yes. Tests for CYP2C9 and VKORC1 are available through most hospital labs and commercial genetic services. Medicare covers them, and many private insurers do too - especially if you’ve had trouble with warfarin before.

How long does genetic testing take?

Results usually come back in 3 to 5 business days. Some labs offer faster turnaround for urgent cases. The test is done with a simple blood or saliva sample.

Do I still need to check my INR if I’ve been genetically tested?

Yes. Genetic testing helps you start at the right dose, but it doesn’t eliminate the need for monitoring. Diet, other medications, illness, and alcohol can still affect your INR. Regular checks are still essential.

Are there side effects to the genetic test itself?

No. The test is a simple lab analysis of your DNA - no needles or procedures beyond what’s needed for a blood draw or saliva kit. There’s no physical risk.

Why do some doctors say genetic testing isn’t worth it?

Some argue that the number of people you need to test to prevent one bleed is high - around 200. But that ignores long-term use. For patients on warfarin for years, especially those with high bleeding risk, the benefit adds up. Also, testing reduces hospitalizations and emergency visits, which saves money overall.

Can I use this test for other blood thinners?

No. These genes only affect warfarin. DOACs like apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran don’t rely on CYP2C9 or VKORC1, so genetic testing doesn’t help with them. The test is specific to warfarin.

What to Do Next

If you’re on warfarin and haven’t been tested, ask your doctor for a referral. If you’re about to start, request testing before your first dose. If your doctor says no, ask why - and push for a second opinion. Your life may depend on it.

Warfarin isn’t perfect. But with genetics, we’re finally starting to treat it like the precision medicine it should be - not a one-size-fits-all shot in the dark.

So if I got the gene test, do I still need to check my INR?

Oh my god, I can't believe people still don't get this. I had a cousin who bled out from a nosebleed because her doctor just guessed her dose. She was 32. Three. Two. And now she's gone. This isn't some abstract science thing - it's people dying because doctors are too lazy to read a genetic report. And don't even get me started on how insurance won't cover it unless you've already almost died. That's not healthcare, that's a death lottery. And the fact that they're still arguing about whether it's worth it? I'm literally shaking right now. This is like refusing to use seatbelts because 'some people survive crashes anyway.' No. No. NO. We have the data. We have the tools. We have the moral responsibility. Stop pretending this is about cost. It's about who you're willing to let die.

While I appreciate the anecdotal evidence presented, the clinical utility of pharmacogenomic-guided warfarin dosing remains statistically marginal when evaluated through the lens of population-level outcomes. The EU-PACT trial, while methodologically sound, demonstrated only a 7.7% increase in therapeutic time-in-range - a metric that, while statistically significant, lacks clinical significance in the context of real-world adherence variability. Furthermore, the 2025 meta-analysis cited fails to account for confounding variables such as dietary vitamin K fluctuation, which exerts a greater effect size than CYP2C9/VKORC1 polymorphisms in over 60% of cases. The assertion that genetic testing reduces hospitalizations is correlational, not causal, and ignores the confounding effect of increased patient monitoring frequency that accompanies testing protocols. Until randomized controlled trials demonstrate a reduction in all-cause mortality - not just bleeding events - routine testing cannot be justified as standard of care.

So let me get this straight - we’re spending $500 to avoid a bleed that might never happen, but we won’t pay $10 a month for DOACs? That’s not science, that’s a scam. Everyone knows warfarin is a relic. Why are we still talking about this like it’s 2010?

You know what’s really dangerous? Not the drug - it’s the system. The pharmaceutical industry doesn’t want you to know your genes because if you did, you’d realize they’ve been selling you a broken product for 70 years. Warfarin was never meant to be personalized - it was designed to be controlled. Who profits when you’re on a stable dose? The labs. The clinics. The insurance companies who charge you $200 every time you get your INR checked. And now they’ve slapped a genetic test on top of it like a Band-Aid on a gunshot wound. They don’t care if you live or die - they care that you keep coming back. They’ve turned your body into a revenue stream. And you’re still thanking them for the test.

My mom got tested after her INR went to 8.5. She’s been on 1.5 mg for 3 years now. No more ER trips. No more panic. I cried when I saw her INR chart finally flatline 😭 Thank you for writing this - I’m sharing it with everyone I know.

Wait - so if you have the AA genotype, you’re basically a walking bleeding risk? That’s why they say Asians are more sensitive to warfarin? Is this why the CDC is quietly pushing genetic screening in Asian communities? And why is the FDA not mandating this for all new prescriptions? This smells like a cover-up. Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know that your DNA makes you a liability. They’d rather you die quietly than admit their one-size-fits-all model is lethal. I’ve seen the documents. They knew. They always knew.

Good info. My uncle in India got tested after a bleed. Dose cut in half. Now he’s fine. Simple.

I get why people are mad about the cost and the bureaucracy but I also think we need to remember that doctors are drowning. They’re not ignoring genetics because they’re lazy - they’re overwhelmed. If the system gave them one click to see the dose recommendation based on genotype, instead of making them dig through PDFs and interpret reports… maybe then it’d actually work. It’s not the science that’s broken. It’s the workflow.

From a clinical pharmacology standpoint, the effect size of CYP2C9/VKORC1 variants is indeed substantial, but the marginal gain in time-in-therapeutic-range must be weighed against the logistical burden of implementation. The cost-per-quality-adjusted-life-year (QALY) for genotype-guided dosing exceeds £15,000 in the UK NHS model - above the typical threshold for cost-effectiveness. Moreover, the pharmacokinetic variability introduced by dietary vitamin K intake and concomitant medications (e.g., trimethoprim) often overshadows the genetic component. While pharmacogenomics holds promise, its current application in warfarin management remains a niche intervention rather than a population-level imperative.

I remember sitting in my doctor’s office after my first INR was 7.2. I was scared. I didn’t know if I’d wake up tomorrow. Then I found out I had the *3 variant. They lowered my dose. I cried. Not because I was scared anymore - because for the first time, someone saw me. Not as a number. Not as a risk. But as someone with a body that works differently. This isn’t just about genes. It’s about being treated like a person. And if you’re on warfarin and haven’t been tested? Please, just ask. It’s not about being perfect. It’s about being seen.

did u know the gmo corn in your cereal affects warfarin? they put it in there to mess with your cyp2c9 so you need more pills. then they charge you more for the test. its all connected. the fda knows. the cdc knows. they just dont tell you. i had to get my dna tested by a private lab in ukraine to find out the truth. they said my genes were 'tampered with'. i think they are watching me now.

Stop wasting money. DOACs exist. Use them. Warfarin is for old people who can’t afford real medicine.

Look, I’ve been doing this for 20 years. I’ve seen 1,200 patients on warfarin. The ones who got tested? They’re fine. The ones who didn’t? Half of them ended up in the ER. I don’t care what the guidelines say. I test everyone now. It’s not about the money - it’s about not being the doctor who let someone die because I was too lazy to order a $300 test. If you’re not doing this, you’re not practicing medicine. You’re just guessing.

It is, however, imperative to underscore the fact that the purported benefits of pharmacogenomic-guided dosing are predicated upon a highly idealized model of clinical implementation - one which assumes perfect adherence to protocol, flawless laboratory turnaround times, and, most critically, an unprecedented level of clinician competency in interpreting complex haplotype data. In reality, the average primary care provider lacks both the training and the cognitive bandwidth to effectively integrate such data into routine practice. Thus, the widespread adoption of this paradigm is not merely logistically untenable - it is epistemologically naive. One cannot simply insert a genetic report into an electronic health record and expect a paradigm shift. The system is not ready. And pretending it is, is not progress - it is performative medicine.