When your heart beats, four valves open and close to keep blood flowing in the right direction. If one of these valves doesn’t work right, it can cause serious problems. Two main issues happen: stenosis and regurgitation. Stenosis means the valve is too narrow. Regurgitation means it leaks. Both force your heart to work harder, and if left untreated, they can lead to heart failure, irregular heartbeats, or even sudden death.

What Is Stenosis? When a Valve Gets Stuck Closed

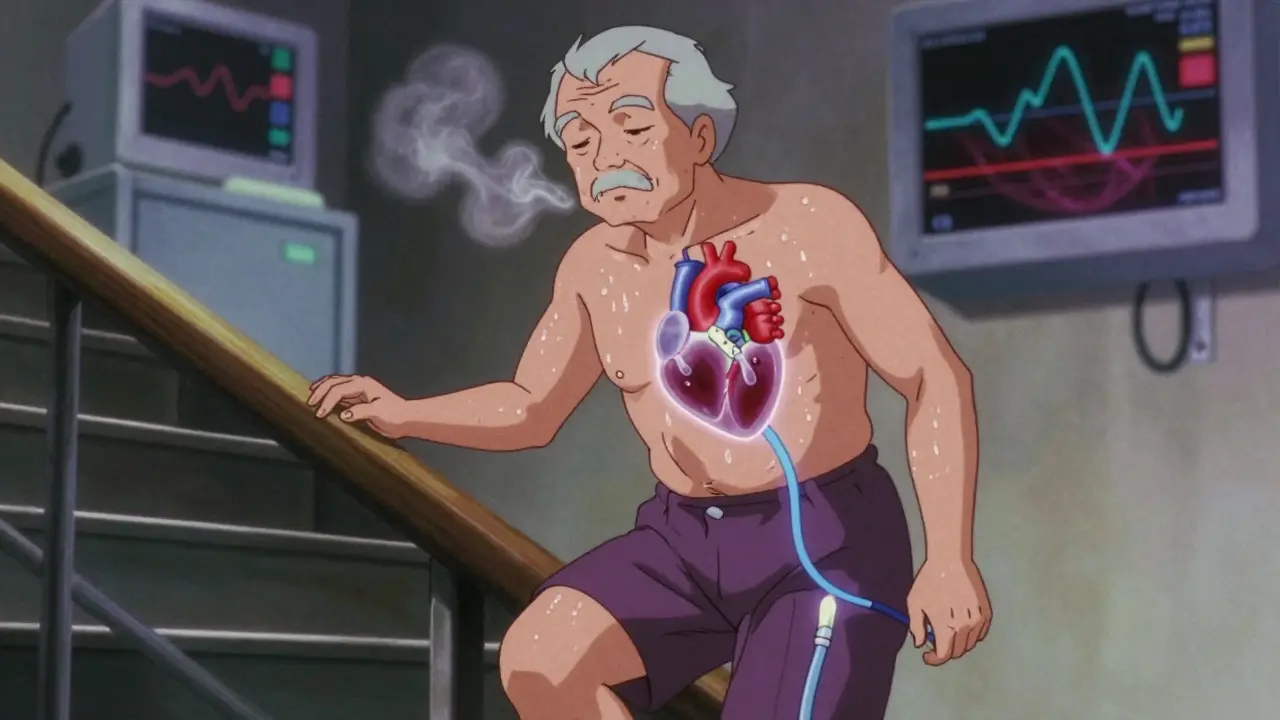

Stenosis happens when a heart valve becomes stiff, thickened, or calcified-like rust on a door hinge. The valve can’t open fully, so less blood flows through. The most common type is aortic stenosis, where the valve between the left ventricle and the aorta narrows. This forces the heart to pump harder to push blood out. Over time, the muscle thickens, gets weak, and can fail.

Severe aortic stenosis is defined by three clear measurements: a valve opening smaller than 1.0 cm², a pressure gradient over 40 mmHg, and blood flow speed exceeding 4.0 meters per second. Most cases (70%) come from aging and calcium buildup. In younger people, a bicuspid aortic valve (a congenital defect where the valve has two leaflets instead of three) causes about half of all cases.

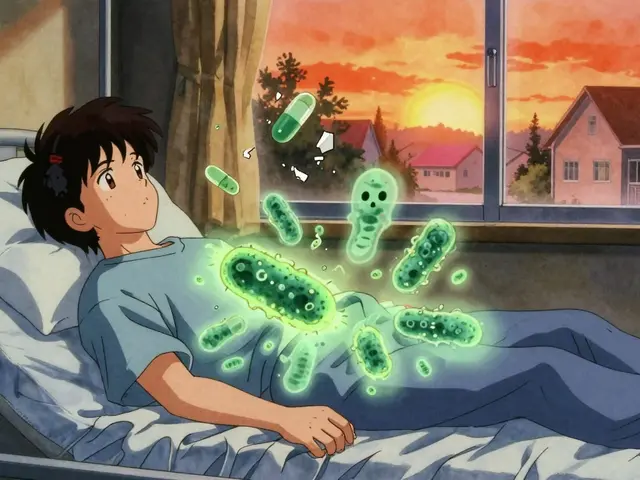

Mitral stenosis is rarer in the U.S. but still common globally. It’s often caused by rheumatic fever, especially in countries without access to antibiotics. When the mitral valve narrows, blood backs up into the lungs, causing shortness of breath, especially when lying down. A valve area under 2.5 cm² is considered abnormal; under 1.5 cm² is severe.

What Is Regurgitation? When Blood Flows Backward

Regurgitation is the opposite problem. Instead of staying shut, the valve leaks. Blood flows backward into the chamber it just left. This doesn’t just waste energy-it overloads the heart.

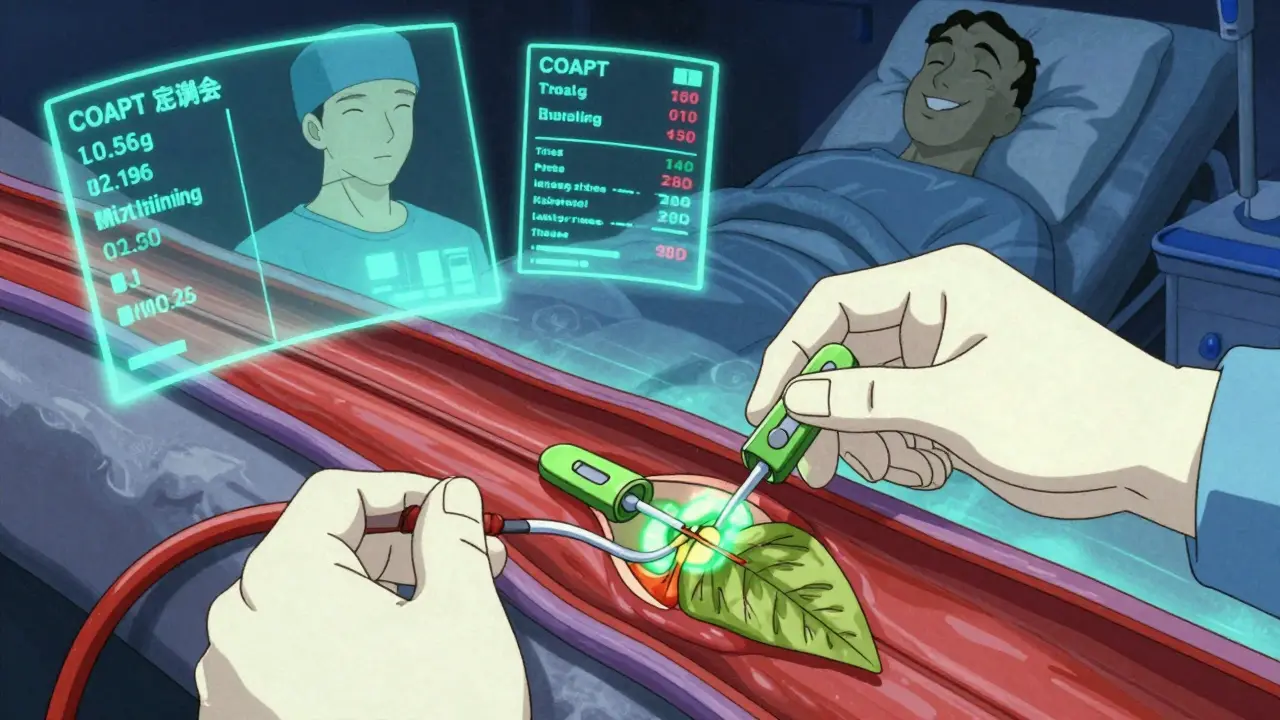

Mitral regurgitation is the most common form. It can be primary (the valve itself is damaged, often from wear, infection, or congenital issues) or functional (the valve is fine, but the heart chamber is stretched and can’t close it properly). In functional cases, the heart’s shape changes, and the valve can’t seal. The COAPT trial showed that for functional regurgitation, a catheter-based repair called MitraClip can cut death risk by 32% compared to medicine alone.

Aortic regurgitation lets oxygen-rich blood leak back into the left ventricle after it’s been pumped out. This causes the heart to hold more blood than normal, stretching the muscle. People often feel their heartbeat strongly (palpitations), get winded during activity, or feel tired even at rest. Unlike stenosis, symptoms can creep in slowly, making them easy to ignore.

How Symptoms Differ Between Stenosis and Regurgitation

Even though both conditions strain the heart, they show up differently.

With aortic stenosis, the classic warning signs are a triad: chest pain (angina) in 54% of cases, fainting (syncope) in 33%, and heart failure symptoms like swelling and breathlessness in 48%. Many patients don’t notice anything until they can’t climb stairs without stopping.

With aortic regurgitation, the main symptoms are shortness of breath during activity (71%) and heart palpitations (29%). Fatigue is common, but people often chalk it up to aging or stress.

Mitral stenosis tends to cause lung congestion-people wake up gasping for air at night (orthopnea) or need extra pillows to sleep. Mitral regurgitation, on the other hand, causes subtle fatigue (reported by 79% of patients) until the heart is severely damaged.

Surgical and Non-Surgical Options Today

Deciding on treatment isn’t just about how bad the valve is-it’s about age, overall health, symptoms, and risk.

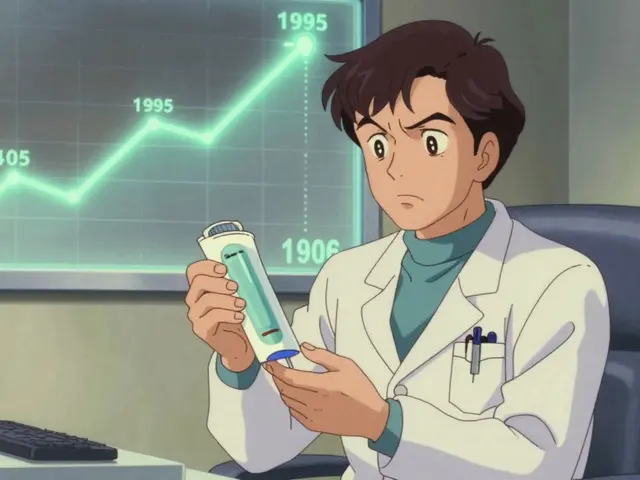

For severe aortic stenosis, the gold standard used to be open-heart surgery to replace the valve. But now, transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is often the first choice. It’s a catheter-based procedure where a new valve is inserted through an artery in the leg or chest. The PARTNER 3 trial showed TAVR reduces death risk by 12.6% compared to surgery in low-risk patients over 75. Today, 65% of aortic valve replacements in the U.S. are done this way in patients over 75.

For mitral regurgitation, surgery is still best for primary cases. The 10-year survival rate after surgical repair is 90%, versus 75% with medicine alone. For functional regurgitation, the MitraClip device is now widely used. It clips the leaflets together without opening the chest. Recovery is faster, and hospital stays are shorter.

For mitral stenosis, balloon valvuloplasty is often the first step. A balloon is inflated inside the valve to stretch it open. It’s quick-about 90 minutes-and most patients go home in two days. But it’s not a permanent fix; about half will need surgery within 10 years.

What Happens After Surgery?

Recovery varies. After open-heart surgery, patients often need 6-8 weeks before lifting heavy things or driving. Pain from the sternotomy (cutting through the breastbone) can last weeks. One patient shared on a support forum: “It took eight weeks before I could lift my grandchildren.”

If you get a mechanical valve, you’ll need lifelong blood thinners. Your INR (a blood test that measures clotting) must be checked twice a week at first, then monthly. Target ranges are 2.0-3.0 for aortic valves and 2.5-3.5 for mitral valves.

If you get a tissue valve (from a pig, cow, or human donor), you won’t need long-term blood thinners-but the valve wears out. About 21% of bioprosthetic valves show signs of deterioration by 15 years. Newer designs are expected to last 25+ years.

Why Timing Matters

Doctors don’t wait for symptoms to get bad before acting. Waiting too long can be deadly. In severe aortic stenosis, if you don’t get treatment, only 50% survive two years. With timely valve replacement, survival jumps to 85% over five years.

But acting too early is risky too. For mild regurgitation without heart damage, surgery may do more harm than good. Experts like Dr. Robert Bonow warn against operating on patients who don’t need it. The key is monitoring. Asymptomatic severe stenosis should be checked with echocardiograms every 6-12 months. Intervention is recommended when the pressure gradient hits 50 mmHg-or when symptoms appear.

What’s New in Valve Care?

The field is moving fast. In March 2023, the FDA approved the Evoque system for tricuspid valve repair-a first for transcatheter treatment of this valve. The Cardioband system, already used in Europe, is in final U.S. trials for mitral repair. The Harpoon system, still in trials, promises to fix leaks without cutting the heart.

By 2030, experts predict 80% of valve procedures will be done without open surgery. The market for heart valve devices is growing fast-projected to hit $9.7 billion by 2029. But access isn’t equal. High-income countries perform 18 procedures per 100,000 people each year. Low-income nations? Just 0.2 per 100,000.

One big concern: many patients feel dismissed until they’re near collapse. A 2022 survey found 28% of valve disease patients weren’t taken seriously until their symptoms were severe. If you have unexplained fatigue, shortness of breath, or chest discomfort-especially if you’re over 65-get checked. A simple echo can catch problems before they’re life-threatening.

Real-Life Impact

One Reddit user wrote: “After my MitraClip, I went from struggling to walk to the mailbox to hiking 3 miles daily in two months.” That’s the difference early, right-sized treatment makes.

Another patient on Inspire.com said: “The hardest part wasn’t the surgery-it was waiting. I thought I was just getting older.” That’s the message: don’t ignore the signs. Your heart is working harder than you think.

What’s the difference between stenosis and regurgitation?

Stenosis means a valve is too narrow and can’t open fully, blocking blood flow. Regurgitation means a valve doesn’t close properly, letting blood leak backward. Both make the heart work harder, but in different ways: stenosis increases pressure, regurgitation increases volume.

Can you live with a leaky heart valve without surgery?

Yes, if the leak is mild and your heart isn’t strained. Many people live for years with mild mitral or aortic regurgitation without treatment. But if the valve is severely leaky or your heart is starting to change shape, surgery or a device like MitraClip becomes necessary. Waiting too long can cause irreversible damage.

Is TAVR better than open-heart surgery?

For most patients over 75 or those with high surgical risk, TAVR is safer and has faster recovery. For younger, healthier patients, open surgery may last longer. But recent data shows TAVR is now preferred even for low-risk patients under 80 because outcomes are nearly identical with less trauma.

How do I know if my valve disease is getting worse?

Watch for new or worsening symptoms: getting winded with less activity, swelling in your legs or belly, chest pain, dizziness, or fainting. If you’ve been diagnosed, regular echocardiograms (every 6-12 months) track changes. Don’t wait for symptoms to be severe-early intervention saves lives.

Do I need blood thinners after valve replacement?

If you get a mechanical valve, yes-you’ll need lifelong blood thinners like warfarin and regular INR checks. If you get a tissue valve, you’ll usually need blood thinners for only 3-6 months. The exact duration depends on your overall risk for clots and the type of valve.

I had aortic stenosis and TAVR at 78. They told me I’d be back to gardening in 6 weeks. I was lifting my cat by week 3. Funny how medicine moves faster than your doctor’s willingness to admit it.

Still, I’m glad I didn’t wait for the ‘classic triad.’ By then, I’d have been too tired to care.

So let me get this straight… we’re replacing heart valves like we swap out a busted toilet flapper? And they call it ‘minimally invasive’? My grandpa had open-heart surgery in ’87 and still talks about the scar like it’s a tattoo from a biker gang. Now we just poke a hole in your leg and slide in a new valve like it’s a USB drive? I’m not mad, I’m just impressed.

There’s a deeper truth here, and nobody wants to talk about it. The heart isn’t just a pump-it’s a sacred organ, a temple of life. But modern medicine treats it like a faulty engine on a production line. TAVR? MitraClip? These aren’t cures. They’re Band-Aids on a crumbling cathedral. We’ve outsourced the soul of healing to corporate medical tech, and now we’re told to be grateful for a ‘faster recovery.’

What happened to the wisdom of waiting? To the body’s innate ability to adapt? We’ve turned death into a product timeline. The real stenosis isn’t in the valve-it’s in our collective willingness to accept technological substitution as progress. And don’t get me started on the profit margins. $9.7 billion by 2029? That’s not innovation. That’s exploitation dressed in white coats.

Just read the COAPT trial data again-32% reduction in mortality for functional MR with MitraClip? That’s not just statistically significant, it’s clinically transformative. Especially when you consider that functional regurgitation is often underdiagnosed because it’s secondary to LV remodeling. The real win here is shifting from ‘fix the valve’ to ‘fix the ventricle.’ We’re finally treating the pathophysiology, not just the echo finding.

Also, the INR targets for mitral mechanicals being higher (2.5–3.5) makes perfect sense-higher shear stress in the left atrium increases thrombogenic risk. Still, I wish more clinicians appreciated how much the valve type dictates anticoagulation strategy. It’s not one-size-fits-all.

TAVR is awesome, but let’s be real-most people don’t even know they have stenosis until they’re gasping on the stairs. My uncle got diagnosed after he passed out at Walmart. No chest pain. No dizziness. Just ‘I think I’m just getting old.’

Doctors need to stop waiting for symptoms. A valve area under 1.0 cm²? That’s not ‘severe.’ That’s ‘emergency waiting to happen.’

I’m from Nigeria, and I’ve seen what happens when you don’t have access to echos or antibiotics. Rheumatic fever still nukes kids’ mitral valves here. One girl I knew-14, no surgery, just pain and coughing at night. She didn’t make it to 18.

It breaks my heart that we’ve got devices that can save lives in real time… and yet 0.2 procedures per 100k in low-income countries? That’s not a medical gap. That’s a moral one.

I thought my fatigue was just from work. Turns out my mitral valve was leaking like a sieve. Got the MitraClip. Now I can carry groceries without stopping. I didn’t even need a hospital bed. Just a little poke and boom-life back. I’m not a doctor but… y’all need to get checked. Seriously.

TAVR? Please. It’s all about the money. The FDA approves these things because the device companies fund the trials. You think they care if your valve lasts 15 years? No. They want you to come back in 5. And don’t get me started on the blood thinners-warfarin is basically poison. They’re keeping you dependent. It’s a trap. They don’t want you cured. They want you subscribed.

I had open-heart surgery in 2019. The sternotomy hurt more than childbirth. Eight weeks of pain. Eight weeks of being told to ‘rest.’ Meanwhile, my neighbor got TAVR and was playing golf two weeks later. The system is broken. They still treat us like we’re 1985. It’s 2024. We have drones, AI, and self-driving cars… but if your heart valve leaks, you still get cut open like a Thanksgiving turkey.