The Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t just change drug policy-it rebuilt the entire system for how generic medicines reach American patients. Before 1984, getting a generic drug approved was nearly impossible. The FDA required full clinical trials for every copy of a brand-name drug, even if the original had already been proven safe and effective. That meant generic companies spent years and millions of dollars just to prove what everyone already knew: the drug worked. Meanwhile, brand-name companies held patents that could last 17 years, and the time spent waiting for FDA approval ate up years of that window. By the time a drug finally hit the market, its patent might be nearly gone. No one won.

What the Hatch-Waxman Act Actually Did

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, solved this stalemate with two simple but powerful ideas. First, it let generic companies skip the expensive, time-consuming clinical trials. Instead, they could prove their drug was bioequivalent-meaning it delivered the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand version. That’s it. No need to retest safety or effectiveness. This cut development costs by about 75% and turned generic approval from a 10-year marathon into a 2- to 3-year sprint.

Second, it gave brand-name companies something back: patent time. The FDA review process often took 5 to 8 years. That meant a drug with a 17-year patent might only have 9 or 10 years of market exclusivity left after approval. Hatch-Waxman allowed innovators to extend their patents by up to 5 years to make up for that lost time. The average extension? Just over 2.6 years. That small tweak gave companies a real incentive to keep investing in new drugs.

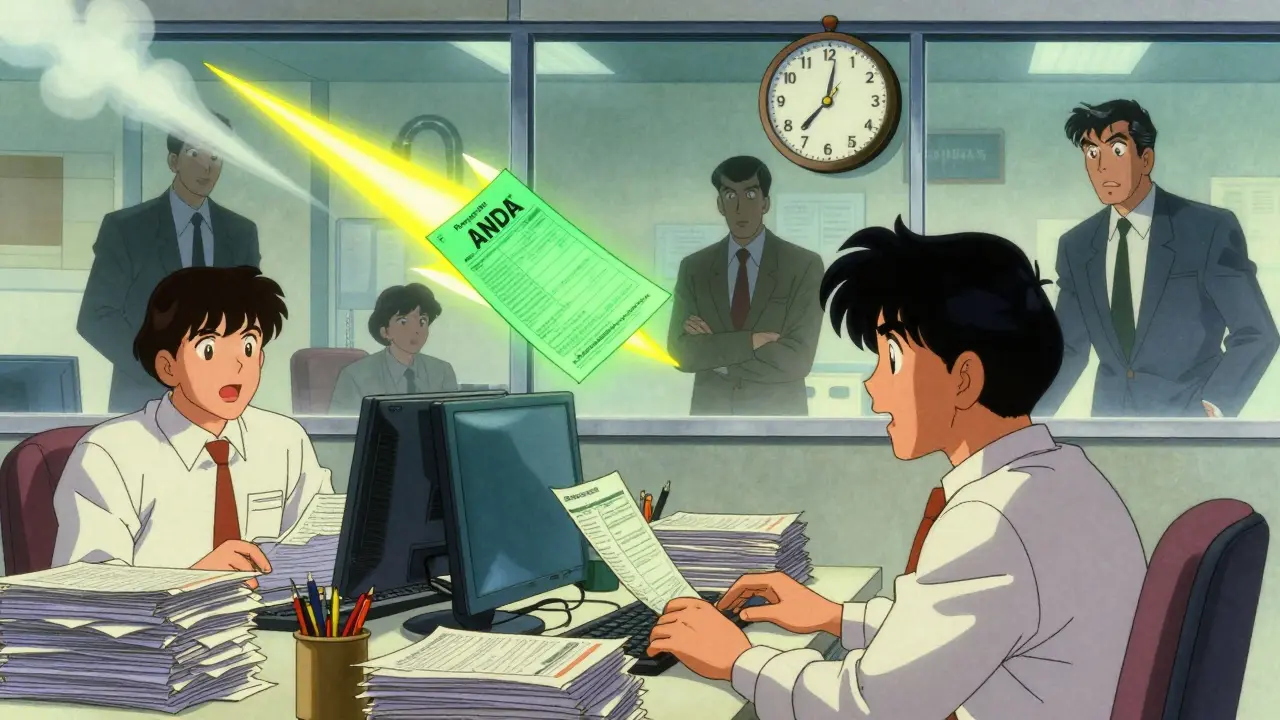

The ANDA Pathway: How Generics Got Their Foot in the Door

The heart of the Hatch-Waxman system is the Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA. This isn’t just a form-it’s a legal shortcut. Generic manufacturers file an ANDA and say: "This drug is the same as the brand version, which the FDA already approved. Here’s our bioequivalence data. Please approve it." The FDA doesn’t redo the original studies. They just check that the generic matches the brand in strength, dosage, how it’s made, and how it’s absorbed by the body.

Before ANDA, fewer than 10 generic drugs got approved per year. In 2019, the FDA approved 771. Today, 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generics. Yet they cost only 18% of what brand drugs do. That’s not luck. That’s Hatch-Waxman.

The Safe Harbor: Why Generics Could Start Before Patents Expired

Here’s where the law got really clever. Before Hatch-Waxman, a generic company could be sued for patent infringement just for testing a drug while the patent was still active. In 1984, the Supreme Court ruled in Roche v. Bolar that even research for FDA approval counted as infringement. That meant generics couldn’t even begin development until the patent expired. The result? No competition for years after patent expiration.

Hatch-Waxman flipped that. Section 271(e)(1) created a legal safe harbor. Generic companies can now make, test, and study patented drugs during the patent term-as long as the only goal is to get FDA approval. This lets them start preparing up to 5 years before a patent runs out. That’s why, today, you’ll often see a generic version hit the market the day after a patent expires. That’s not magic. That’s the safe harbor in action.

Paragraph IV: The Nuclear Option in Generic Drug Battles

But here’s the twist: not every patent is bulletproof. Hatch-Waxman lets a generic company challenge a listed patent by filing a Paragraph IV certification. This says: "We believe this patent is invalid or we won’t infringe it." When that happens, the brand company has 45 days to sue. If they do, the FDA is legally required to delay approval for 30 months-unless the court rules faster.

This created a new kind of race. The first generic company to file a Paragraph IV certification gets 180 days of exclusive marketing rights. No other generic can enter during that time. That’s worth billions for blockbuster drugs. In the 1990s and early 2000s, companies would camp out overnight outside FDA offices to be the first to submit. The FDA changed the rules in 2003 to allow multiple companies to share the exclusivity if they filed on the same day. But the incentive remains. It’s still the single biggest financial prize in generic drug development.

How the System Got Gamed

Like any system with money and patents involved, Hatch-Waxman got exploited. Brand-name companies started filing dozens of patents on minor changes-like a new pill coating, a slightly different dose, or a new use for an old drug. These are called "secondary patents." In 1984, the average drug had 3.5 patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. By 2016, that number had jumped to 2.7 per drug. Wait-that’s not right. Actually, it jumped to 14 patents per drug. That’s a fourfold increase.

This created "patent thickets." Instead of one big patent blocking generics, companies stacked 10, 12, even 20 small ones. Each one had to be challenged separately. Legal costs for a single Paragraph IV challenge now average $15 million to $30 million. That’s why some generic companies say the 180-day exclusivity window is useless if they’re stuck in court for seven years.

Then there’s "product hopping." A brand company makes a tiny change to its drug-say, switching from a pill to a tablet-and then patents that new version. They stop selling the old one, pushing patients onto the new, still-patented version. Generics can’t copy the new version until that patent expires. This delays competition without creating any real medical benefit.

And then there’s "pay-for-delay." A brand company pays a generic company to delay launching its cheaper version. Between 2005 and 2012, these deals happened in 10% of all patent challenges. The FTC called them anti-competitive. Congress tried to ban them with the 2023 Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act. It passed the House. It’s still stuck in the Senate.

Who Benefits? Who Loses?

On paper, Hatch-Waxman is a win-win. Patients get cheaper drugs. Companies get to innovate. But the reality is messier.

Patients win. The U.S. healthcare system saved $1.18 trillion between 1991 and 2011 because of generic drugs. Today, generics save $313 billion every year. That’s money that goes back into hospitals, doctors’ offices, and patients’ pockets.

Generic manufacturers win too-but only the big ones. In 2000, the top 10 generic companies controlled 38% of the market. By 2022, that jumped to 62%. Small companies can’t afford the legal battles or the 24-to-36-month preparation time for an ANDA. The system favors scale.

Brand companies win in the short term. The average effective market exclusivity for a new drug went from 10.4 years in 1984 to 13.2 years today. That’s thanks to patent extensions, thickets, and delays. But they pay a cost: innovation slowed. R&D spending per approved drug jumped from $138 million in 1984 to $2.3 billion in 2022. Are we getting better drugs? Or just more expensive ones?

What’s Changing Now?

The FDA is trying to fix the system. Under GDUFA IV, they aim to cut ANDA review times from 10 months to 8 months by 2025. They’re also cracking down on improper patent listings. In 2022, they released new draft guidance saying patents on inactive ingredients or methods of use can’t be listed unless they directly relate to the drug’s approved use.

States are stepping in too. California, New York, and others passed laws to stop product hopping. The CREATES Act of 2022 forced brand companies to provide samples to generic makers-something some had been refusing to do to delay competition.

But the biggest challenge remains: how to keep innovation alive without letting patents become a tool for monopoly. The system works. But it’s been stretched thin. The original compromise was elegant. Now, it’s a battleground.

Why It Still Matters

Without Hatch-Waxman, most of the drugs you take today would cost 5 to 10 times more. Insulin. Blood pressure pills. Cholesterol meds. Antibiotics. All of them would be priced like brand-name biologics. The Act didn’t just lower prices-it made medicine accessible.

It also created a model the world followed. The EU, Canada, Japan-all built their generic systems around the same idea: prove bioequivalence, not re-prove safety. That’s why the U.S. gets generics to market faster than most other countries.

But the game is changing. Patents are longer. Lawsuits are costlier. The stakes are higher. The Hatch-Waxman Act wasn’t perfect. But it was the right foundation. Now, we just need to fix the cracks before the whole structure starts to lean.

So basically Hatch-Waxman was the first time the government said 'we trust science, not lawyers' and it worked? Wild.

Oh sweet Jesus, another post pretending this was some noble bipartisan compromise. Let’s not forget the 1984 Senate was packed with pharma lobbyists who wrote half the bill themselves. The 'safe harbor'? More like a velvet rope for Big Pharma’s BFFs. And don’t get me started on Paragraph IV - it’s not innovation, it’s litigation roulette with taxpayer-funded stakes. You call this a system? It’s a casino with a FDA stamp on the table.

As someone from India where generics are the backbone of healthcare, I find this fascinating. The ANDA system is why drugs like insulin cost $15 here and $300 in the U.S. But the patent thickets? That’s a corporate tactic I’ve seen replicated globally. The real tragedy isn’t the law - it’s how it’s weaponized. The original intent was brilliant. The execution? A corporate playbook written by lawyers with stock options.

My grandma takes six generics a day. She wouldn’t be alive without this law. I don’t care about the loopholes - it works. People get medicine. That’s the point.

patent thickets = pharma’s version of a maze with spikes

I’ve worked in clinical trials and can confirm the old system was a nightmare. Imagine spending 8 years proving something you already know works. Hatch-Waxman didn’t just fix a process - it saved lives by making the system human again. Yeah it got gamed, but the core idea? Still flawless

THIS. IS. WHY. I. LOVE. AMERICA. 🇺🇸👏 Generics saved my kid’s asthma meds from costing $800 a month. Thank you, Hatch-Waxman. 🙌

Let’s not romanticize this. The 180-day exclusivity window isn’t competition - it’s a monopoly disguised as incentive. And the pay-for-delay deals? That’s not capitalism, that’s collusion with a law degree. The system was designed to balance innovation and access. Now it’s just a balance sheet for shareholders.

Oh so the FDA is now 'cracking down' on patent listings? Funny, they spent 20 years letting pharma list patents for 'color of the pill' as if that’s a medical breakthrough. Wake up. This isn’t reform - it’s damage control after the house burned down.

Big Pharma’s patent games are real but don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. The ANDA system still delivers 90% of prescriptions at 18% cost. That’s not broken - it’s just being hijacked. Fix the loopholes, don’t dismantle the engine.

Let me tell you what’s REALLY happening - the FDA is being starved of funding while pharma hires ex-agents as consultants. The system isn’t broken, it’s been sabotaged by the very people who were supposed to guard it. And now they’re acting surprised? Please. This was a heist with a press release.

As someone who’s seen healthcare systems in 12 countries, the U.S. still leads in generic access - even with all the flaws. India makes the pills, but America figured out how to make them legally available at scale. That’s not nothing. We just need to stop letting lawyers run the pharmacy.

so basically the law was genius… until everyone started cheating? classic. 🤦♀️ but hey at least the pills are cheaper than my Netflix subscription

What’s clear is this: Hatch-Waxman created a system that works for patients. The problem isn’t the law - it’s the people who treat it like a game. We need enforcement, not overhaul. Let’s punish pay-for-delay. Let’s ban product hopping. Let’s fund the FDA. Then we’ll see real change - without throwing out the baby, the bathwater, or the bathtub.