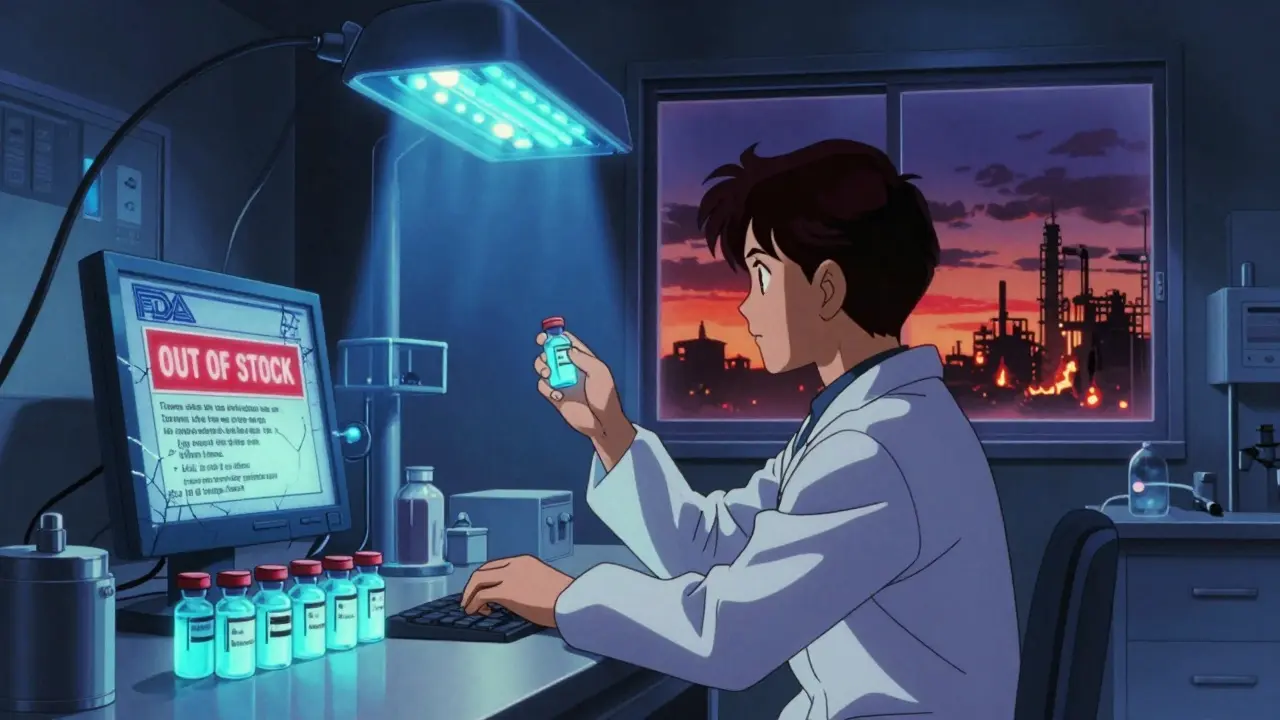

It’s 2025, and your doctor prescribes a generic antibiotic you’ve taken for years. You show up at the pharmacy, and they say it’s out of stock. No replacement. No timeline. Just silence. This isn’t rare. It’s happening more often - not because there aren’t enough generic drugs, but because there are too many companies chasing the same low-margin products, and too few willing to make the hard-to-produce ones.

Why Do Generic Drugs Even Exist?

Generic drugs are the backbone of affordable healthcare. When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, any manufacturer can copy it. They don’t need to run expensive clinical trials - just prove it works the same way. The FDA approves these copies through an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). In 2023 alone, the FDA approved 956 of them. That’s more than two per day.And it works. Nine out of every ten prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics. They’re not cheaper because they’re worse - they’re cheaper because they don’t carry the cost of discovery, marketing, or patent protection. The savings are massive. In 2023, generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system $313 billion, according to UnitedHealthcare.

The Price Drop That Broke the System

Here’s the catch: when a new generic hits the market, prices don’t just drop - they crater. In markets with three or more competitors, prices fall by about 20% within three years. With five or more, they can drop 80% or more from the original brand price. That sounds great - until it doesn’t.For simple pills like metformin or lisinopril, dozens of companies compete. The price per pill can be less than a penny. But making a pill costs money. Raw materials. Labor. Quality control. Compliance. Packaging. Shipping. When the price drops below the cost to produce, companies stop making it. And they do - quietly. One by one, they exit the market.

That’s why, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, prices for 50 commonly used generics have actually gone up by 15.7% annually since 2018. Not because of inflation. Because manufacturers left. Fewer makers = less competition = higher prices. The market doesn’t collapse from too little supply. It collapses from too many players chasing the same low-margin products, and none left to make the ones nobody wants to make.

The Real Problem: Complex Drugs and Few Makers

Not all generics are created equal. A tablet you swallow is easy to copy. A sterile injectable you get in the hospital? Not so much.Producing injectables like epinephrine, vancomycin, or chemotherapy drugs requires clean rooms, aseptic processing, and millions in equipment. One facility can cost $200-500 million to build and take 18-24 months to get approved. Only a handful of companies have the capacity. In the sterile injectables market, just five manufacturers control 46% of the supply.

When one of them shuts down - because of an FDA warning letter, a quality failure, or just because it’s no longer profitable - the entire market stumbles. That’s what happened in 2023 with generic epinephrine auto-injectors. One major plant was shut down for data integrity violations. No one else could ramp up fast enough. Patients with severe allergies were left without life-saving medication.

And it’s not just injectables. Antibiotics, heart medications, and oncology drugs are all at risk. The American Medical Association found that 78% of physicians experienced at least one generic drug shortage in 2023. Nearly half said it directly impacted patient care.

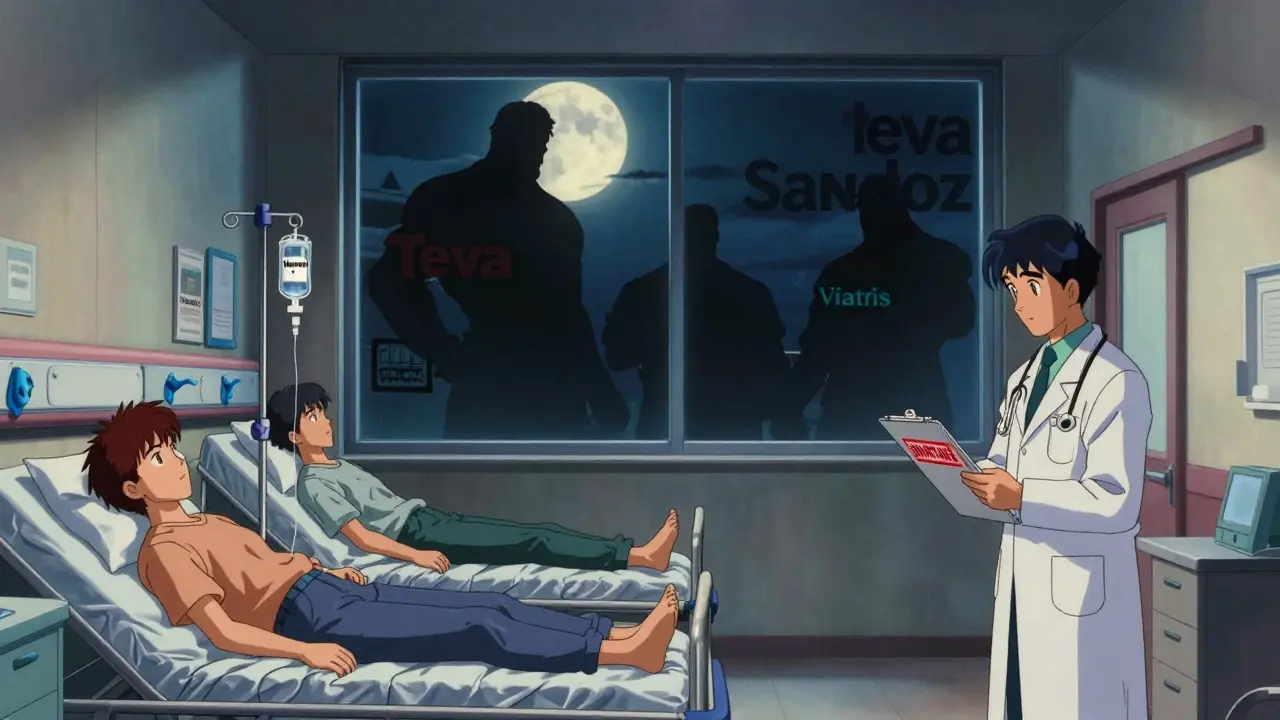

Who’s Left Standing?

The market isn’t empty. It’s concentrated. Teva, Viatris, Sandoz, Sun Pharma, Aurobindo, and Fresenius Kabi dominate. But they don’t make everything. They pick the winners - the high-volume, low-complexity drugs with just enough margin to survive. They ignore the ones that are hard to make, low-demand, or low-priced.That’s why there are 15-20 big generic manufacturers globally, but only 1-3 making specific essential drugs. IQVIA found that 35% of generic drug markets have fewer than three active suppliers. Twelve percent have just one. One. If that one plant has a power outage, a supply chain hiccup, or a regulatory inspection, the drug vanishes.

Regulators Are Trying - But They’re Fighting a Losing Battle

The FDA knows this is a problem. Their Drug Competition Action Plan has increased first-generic approvals by 40% since 2017. More competition should mean more supply, right?Not always. Many of those new entrants are copycats of the same easy-to-make drugs. Meanwhile, the number of FDA warning letters for data fraud and quality failures jumped 23% in 2023. Some manufacturers cut corners to survive the price war. Others just walk away.

The European Medicines Agency says the sweet spot for supply security is 4-6 manufacturers per essential drug. Right now, only 65% of essential generics meet that standard. The rest? One or two makers. That’s not competition. That’s a single point of failure.

The Inflation Reduction Act Is Coming - And It Will Make Things Worse

Starting in 2026, the U.S. government will start negotiating prices for 10 high-cost drugs. The plan? Lower prices for patients. Sounds good - until you realize most of these are already generic.That means even less margin for manufacturers. For drugs already on the edge of profitability, this could be the final push. Mordor Intelligence estimates the new price controls will squeeze generic margins by 15-25%. That’s not a tweak. It’s a hammer.

What happens next? More exits. Fewer makers. More shortages. The irony? The law meant to help patients could make drug access worse for the most vulnerable.

What Can Be Done?

This isn’t unsolvable. But it needs smarter policy - not just more competition.- Strategic stockpiles: Governments should maintain reserves of critical generics - not just for emergencies, but for routine supply gaps.

- Guaranteed minimum prices: For essential, low-margin drugs, set a floor price that covers production costs. No more race to the bottom.

- Financial incentives: Reward manufacturers who make complex or low-profit drugs. Tax credits. Subsidies. Guaranteed purchase agreements.

- Regional manufacturing: Stop relying on one country for 80% of the world’s generics. Build capacity in North America and Europe for critical drugs.

India and China make most of the world’s generics. That’s efficient - until a pandemic, a trade war, or a quality scandal cuts off supply. The U.S. and EU are waking up to this. But they’re moving too slowly.

It’s Not About Too Few Makers - It’s About Too Few Willing Makers

We think the problem is too few companies making generics. But that’s not it. There are plenty. The problem is too many making the same easy drugs - and too few willing to make the hard, low-profit ones that keep hospitals running.Competition isn’t bad. It’s necessary. But competition without sustainability is just a race to the bottom. And when the bottom is a hospital pharmacy with no epinephrine, no antibiotics, no chemo - then everyone loses.

Healthcare isn’t a commodity market. Drugs aren’t toothpaste. When a life-saving generic disappears, it’s not an inconvenience. It’s a crisis. And we’re running out of time to fix it before the next one hits.

Let’s be real - we’ve turned life-saving medicine into a commodity auction where the lowest bidder wins, even if they can’t actually deliver. The FDA approves generics like they’re approving new flavors of yogurt, but no one’s accounting for the cost of maintaining sterile facilities or the human labor behind every vial. It’s not a market failure - it’s a moral failure disguised as capitalism.

From a pharmacoeconomic standpoint, the current ANDA-driven paradigm exhibits severe structural inefficiencies - particularly in oligopolistic markets where economies of scale collapse under price elasticity thresholds. The absence of cost-based price floors incentivizes predatory de-risking behavior among manufacturers, leading to strategic supply withdrawal. We need regulatory intervention that recognizes therapeutic essentiality, not just volume metrics.

My grandma couldn’t get her heart med last month. Took three pharmacies. She cried. This isn’t policy. This is negligence.

Let me break this down numerically: 80% of generic APIs come from India and China. 23% increase in FDA warning letters since 2020. 35% of essential generics have fewer than three suppliers. The correlation isn’t coincidental - it’s systemic. And the IRA’s price caps? That’s the final nail. Margins are already negative for 12% of essential generics. This isn’t a crisis - it’s a countdown.

India produces generics efficiently, but quality control is inconsistent. Nigeria’s importers often get substandard batches. We need traceability - not just more manufacturers. If a pill can’t be tracked from factory to pharmacy, it shouldn’t be approved.

People act like this is new, but it’s been happening since the 2010s. I worked in pharma logistics. Companies would drop a drug the second the price hit $0.02/pill. No warning. No notice. Just ‘out of stock’ on the portal. We knew it was coming. No one did anything.

The real issue is the misalignment between regulatory incentives and manufacturing realities. The FDA prioritizes approval speed over supply chain resilience. Meanwhile, manufacturers optimize for ROI, not public health. We need a tiered approval system: fast-track for high-volume, low-risk; slow-track with subsidies for complex, low-margin critical drugs. Simple.

I know it sounds bleak, but we’ve solved worse. Remember when insulin was unaffordable? People rallied. States passed laws. Companies were shamed into action. We can do the same here. It’s not about more competition - it’s about smarter competition. Let’s fund the makers of the hard stuff. Reward them. Protect them. They’re the real heroes.

As someone who’s seen this play out in Lagos and Atlanta - the global supply chain isn’t broken. It’s rigged. The same few conglomerates own the API factories, the packaging plants, the shipping lanes. They let small players fail so they can buy up the patents later. This isn’t free market. It’s corporate consolidation with a FDA stamp.

This is the inevitable outcome of deregulation, outsourcing, and the erosion of American industrial capacity. The government abandoned domestic manufacturing in favor of ‘efficiency,’ and now we’re paying the price with patients’ lives. The fact that we rely on foreign entities for life-saving injectables is not just irresponsible - it’s treasonous. We need a national pharmaceutical industrial policy - immediately. No more compromises.

Did you know the FDA is secretly controlled by Big Pharma? They approve generics to flood the market, then let prices crash so people get hooked on cheap meds - then they raise prices on the brand-name versions under new patents. It’s all a scheme. The IRA? That’s just to distract us while they move the supply chains to private prisons. You think they care about epinephrine? No. They care about control.

The European model is instructive: mandatory stockpiles, strategic procurement contracts, and tiered pricing based on therapeutic necessity. Why are we reinventing the wheel? We have the data. We have the precedent. What we lack is political will - and perhaps, moral courage.

My cousin in Mumbai works at a generic plant. They make metformin for $0.003 a pill. The workers get paid $3 a day. The CEO makes millions. This isn’t about competition - it’s about exploitation. We need global labor standards in pharma. No more race to the bottom - especially not on medicine.

It is my considered opinion, based upon empirical observation and longitudinal analysis of pharmaceutical market dynamics, that the current paradigm of unregulated generic drug proliferation constitutes a systemic failure of public health governance. The absence of mandatory minimum production thresholds, coupled with the absence of enforceable supply chain redundancy protocols, renders the entire enterprise vulnerable to stochastic disruption. A structural recalibration is not merely advisable - it is an ethical imperative.