Working out with diabetes doesn’t have to mean avoiding movement because you’re scared of crashing. But if you’ve ever felt shaky, sweaty, or dizzy mid-run - or worse, woke up in the middle of the night with a low after a good day of activity - you know the fear is real. About 50% of people with type 1 diabetes skip exercise because they’re afraid of hypoglycemia. It’s not just anxiety. It’s based on real biology. The good news? You can train your body, plan smarter, and move confidently without lows.

Why Exercise Drops Your Blood Sugar

When you move, your muscles don’t wait for insulin to grab glucose. They pull it straight from your bloodstream to fuel the effort. That’s a good thing - it’s how your body stays efficient. But for someone on insulin, this extra demand can tip the scales too far. Your liver usually steps in to release stored sugar, but insulin suppresses that response. So if you’ve got insulin on board - especially from a recent bolus - your blood sugar can plummet fast. The drop doesn’t stop when you finish. Your muscles keep pulling glucose for hours, sometimes up to 72 hours, to refill their energy stores. That’s why a 3 p.m. bike ride can leave you crashing at 2 a.m. And that’s not a fluke. 70% of people with type 1 diabetes experience delayed lows after exercise, according to research in Diabetes Care.When to Check Your Numbers - And What to Do

Don’t guess. Check. The American Diabetes Association says check your blood sugar 15 to 30 minutes before you start. If it’s below 90 mg/dL, you’re in the danger zone. At that point, eat 15-20 grams of fast-acting carbs - think 4 glucose tablets, half a banana, or 6 oz of regular soda. Wait 15 minutes. Check again. If it’s still under 100, eat another 15 grams. If your number is between 90 and 150 mg/dL, you’re in the safe-but-needs-a-buffer range. Eat the same 15-20 grams of carbs before you start. You’re not trying to spike - you’re just building a cushion. During longer workouts - anything over 30 minutes - check every 30 to 60 minutes. Even if you feel fine. Lows can sneak up silently, especially if you’re in a flow state or distracted by music or conversation.Timing Matters More Than You Think

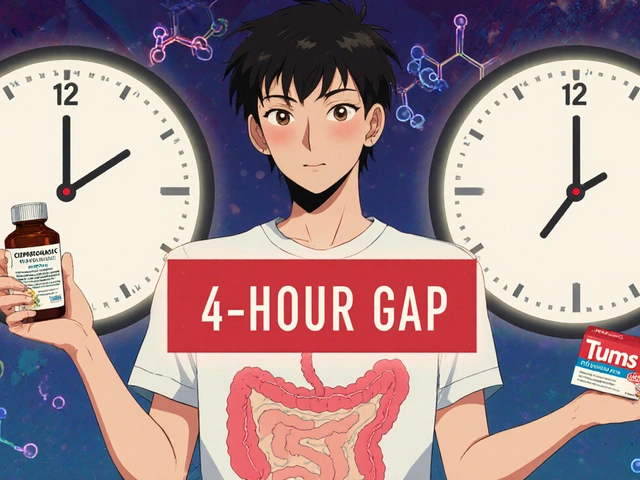

Exercise at the same time every day if you can. Why? Because insulin peaks at predictable times. If you always take your breakfast bolus at 8 a.m., and you work out at 7 a.m., you’re likely hitting your workout right as insulin is strongest. That’s a recipe for a crash. Instead, aim for 1-2 hours after a bolus, when insulin is winding down. Or, if you’re on a pump, reduce your basal rate. Most people cut it by 50-75% starting 60-90 minutes before moderate exercise. That’s not a guess - it’s clinical protocol backed by T1D Exchange data. If you’re on multiple daily injections, reduce your pre-workout bolus by 25-50%. Don’t skip it entirely unless your number is already high. You still need some insulin to prevent ketones, especially if you’re doing longer sessions.

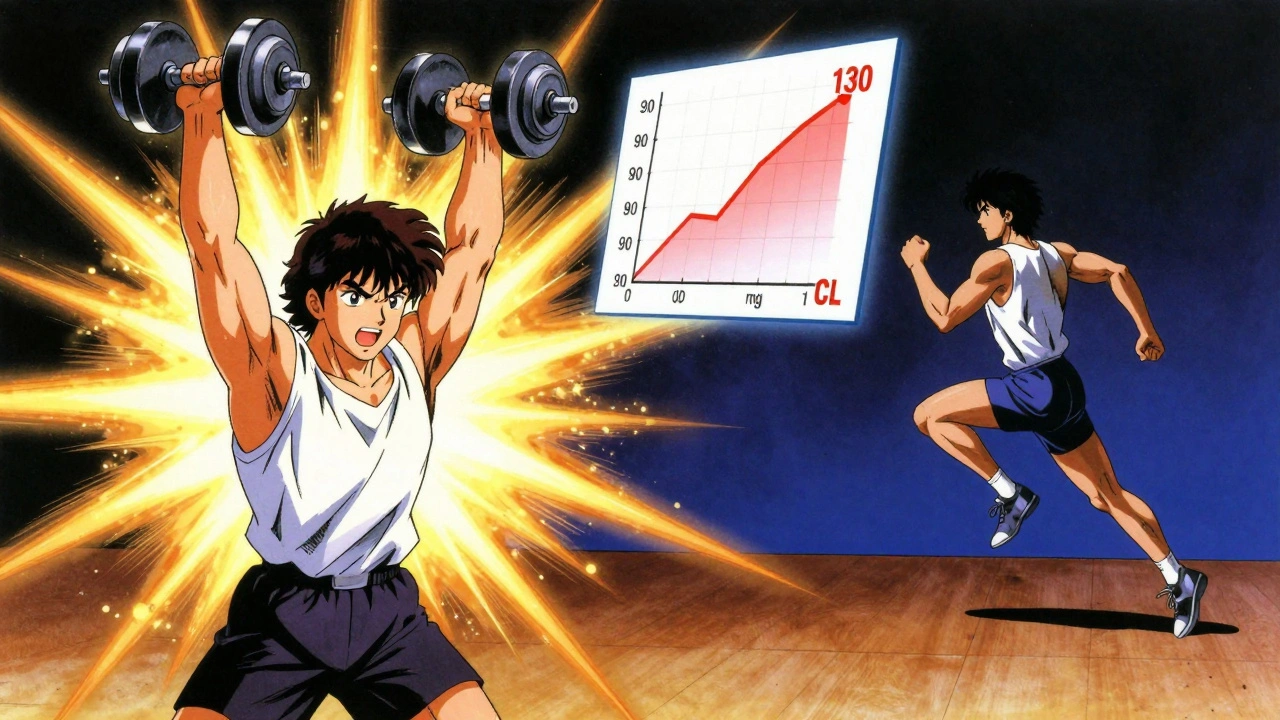

Not All Workouts Are Created Equal

Here’s where most people get it wrong. They think cardio is the only option - and then wonder why they’re always low. Not all exercise affects blood sugar the same way. Aerobic exercise - running, cycling, swimming - steadily lowers glucose. It’s predictable. But it’s also the biggest culprit behind lows. Resistance training - lifting weights, bodyweight circuits - can actually raise blood sugar temporarily. Why? Because your body releases stress hormones like adrenaline to fuel the effort. That’s a gift. A 2018 study found that doing 45 minutes of resistance training before 45 minutes of cardio cut glucose drops from 166 to 124 mg/dL - compared to dropping from 166 to 105 without it. That’s a 19-point buffer. High-intensity intervals - think 30 seconds of sprinting, 90 seconds of walking - are your secret weapon. Research shows just a 10-second all-out sprint before or after your workout can blunt the drop. One user on Reddit said adding a quick bike sprint cut his weekly lows from four to one every two weeks. That’s not magic. It’s biology. Circuit training with minimal rest? That’s riskier. It blends aerobic and resistance, and the constant motion can drain glucose fast. If you do it, check more often and have carbs handy.Technology Is Your Ally - But Not Your Crutch

If you use a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), you’re already ahead. But don’t just rely on alerts. Use the features. Dexcom’s G7 has an “exercise mode” that lowers alert thresholds by 20 mg/dL during activity - so you get warned earlier. Tandem’s t:slim X2 pump now has an “Exercise Impact” feature that uses AI to predict glucose drops based on your past workouts and adjusts insulin automatically. But tech only works if you feed it good data. You need to log your workouts, carbs, insulin, and glucose changes. Over time, your CGM or pump learns your patterns. One user told me he started logging his 5K runs with exact times, insulin doses, and pre-workout snacks. After three weeks, his pump started suggesting a 40% basal reduction before every run - and he hasn’t had a low since.The Nighttime Low Trap

This is the silent killer. You had a great workout. You checked your sugar before bed. It was 130. You went to sleep. Two hours later, you wake up at 52. You’re drenched in sweat, heart racing. You didn’t see it coming. Why? Because your muscles kept pulling glucose all night. You didn’t eat enough to cover the delayed drop. The fix? A bedtime snack with carbs and protein. Not just a granola bar. Think: 15g carbs + 10g protein. A small apple with peanut butter. A cup of cottage cheese with a few berries. The protein slows digestion, giving you a longer, steadier release of glucose. And yes - check your glucose again at 2 a.m. if you exercised hard in the afternoon. It’s not paranoia. It’s prevention.

What Works for Others - And What Doesn’t

You’ll hear all kinds of advice. “Just eat more carbs.” “Don’t take insulin before workouts.” “Do yoga instead.” None of those are universal truths. One person swears by eating a banana before every run. Another eats nothing and uses a 75% basal reduction. Both work - because they’re personalized. Your body responds differently than mine. Your insulin sensitivity, your activity level, your sleep, your stress - all of it changes how you react. The key is tracking. Write down:- What you did (type, duration, intensity)

- What you ate before and during

- Your insulin dose (bolus + basal)

- Your starting glucose

- Your lowest glucose during or after

Start Small. Build Confidence.

You don’t need to run a marathon tomorrow. Start with a 20-minute walk. Check your sugar before, during (if you can), and after. Eat 15g carbs if you’re under 100. See what happens. Try a short resistance session next - 10 minutes of squats and push-ups. Then try combining them: 10 minutes lifting, then 20 minutes walking. It takes 3 to 6 months to really learn your body’s response. But every time you move safely, you build confidence. Every time you prevent a low, you prove to yourself that diabetes doesn’t own your movement.Final Rule: Always Have Carbs Nearby

No matter how experienced you are. No matter how good your tech is. Always carry fast-acting carbs. Glucose tabs. Juice boxes. Gummies. Something you can grab in 3 seconds if you feel off. And tell someone where you’re going. Even if it’s just a text: “Going for a bike ride. Back in 45.” You’ve got this. Movement isn’t the enemy. It’s medicine. You just need to dose it right.Can I exercise if my blood sugar is below 70 mg/dL?

No. If your blood sugar is below 70 mg/dL, treat it first with 15 grams of fast-acting carbs. Wait 15 minutes, check again. Only start exercising once your number is at least 100 mg/dL. Exercising while low can make it worse and increase the risk of passing out or injury.

Should I reduce my insulin before exercise?

Yes, for most people on insulin, reducing insulin before exercise helps prevent lows. If you use a pump, lower your basal rate by 50-75% starting 60-90 minutes before moderate activity. If you use injections, reduce your pre-workout bolus by 25-50%. Always consult your healthcare provider to personalize this based on your insulin sensitivity and workout intensity.

Do I need to eat carbs during exercise?

If your workout lasts longer than 30 minutes and your blood sugar is below 150 mg/dL, yes. Aim for 0.5-1.0 gram of carbs per kilogram of body weight per hour. For a 70 kg person, that’s about 35-70 grams per hour - broken into smaller doses every 20-30 minutes. Use glucose gels, sports drinks, or easily digestible snacks. Don’t wait until you feel low to eat.

Why do I get low hours after working out?

After exercise, your muscles are refilling their glycogen stores - and they pull glucose from your blood without needing insulin. This process can last up to 72 hours. That’s why a workout at 4 p.m. can cause a low at 2 a.m. To prevent this, have a bedtime snack with carbs and protein, and consider checking your glucose around midnight if you exercised hard that day.

Is HIIT safer than steady cardio for people with diabetes?

Yes, for many people. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) triggers adrenaline release, which temporarily raises blood sugar. Short bursts of all-out effort - like 10-30 seconds of sprinting - can block the glucose drop that follows steady cardio. Studies show adding a 10-second sprint before or after a workout reduces hypoglycemia risk during and after exercise. It’s not a cure-all, but it’s one of the most effective tools in your toolkit.

Can I use my CGM to predict lows during workouts?

Modern CGMs like Dexcom G7 and Abbott Libre 3 can detect trends and alert you to fast drops. Some pumps, like Tandem t:slim X2 with Exercise Impact, use AI to predict glucose changes based on your history and activity type. But no system is perfect. Always confirm with a fingerstick if you feel symptoms, especially when starting a new workout. Tech helps - but your body’s signals still matter most.

Just wanted to say how much I appreciate the breakdown on delayed lows. I used to think I was doing something wrong when I’d crash at 3 a.m. after a morning run. Turns out, it’s biology-not failure. Now I keep cottage cheese and berries by my bed. Game changer. 🙌

There’s a deeper truth here that doesn’t get said enough: movement isn’t just medicine-it’s reclaiming autonomy. Diabetes tries to turn your body into a problem to be solved, but every time you lace up and step out, you’re saying, ‘I’m not defined by my numbers.’ That’s the real win.

Ok but have y’all heard about the government’s secret plan to make diabetics exercise so they stop using insulin? 😏 I’m not saying it’s true but… why do all the ‘experts’ always say ‘just move more’? 🤔 #BloodSugarConspiracy

While the article presents a comprehensive framework for managing exercise-induced hypoglycemia, it fails to account for inter-individual variability in insulin pharmacokinetics across diverse populations. The recommended 50-75% basal reduction is statistically derived from predominantly Caucasian cohorts and may not be universally applicable. Further ethnopharmacological validation is warranted.

HIIT saved my life. 10 sec sprint before a run? No more 2 a.m. crashes. Just do it. 💪

I used to hate checking my sugar before workouts. Felt like I was being punished for wanting to move. Then I realized-this isn’t about control. It’s about respect. For your body. For your future self. You don’t have to be perfect. Just show up. And carry the glucose tabs. Always.

For anyone doing longer endurance sessions, don’t forget about electrolytes. Sodium and potassium loss during sweat can worsen hypoglycemia symptoms even if your glucose is technically in range. I keep a pinch of salt in my water bottle and a banana on hand-works like magic. Also, logging workouts in MySugr changed everything for me. Patterns emerge when you stop guessing.

Love this. I started with 10-minute walks and now I’m training for a half-marathon. Took 8 months. No magic. Just consistency. And carbs. Always the carbs. 😊